Barnard College is requiring students to strip decorations from their dorm doors in the wake of protests over the Israel-Hamas war.

Dorm door decorations are emerging as the next battleground in the fight over academic freedom and free speech at Barnard College.

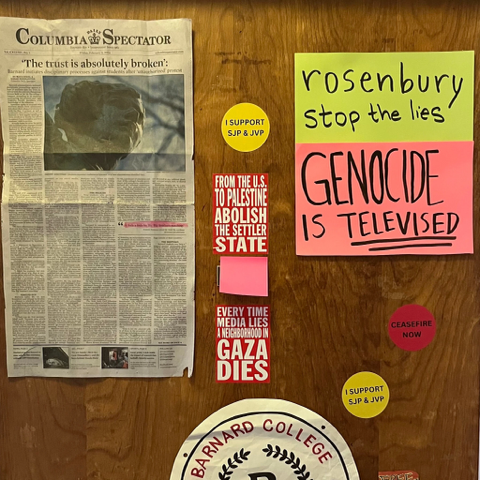

As at many schools, Barnard students often use their dorm doors to display a bit of personality. A walk around the freshman dorms early this week found sorority pledge signs, Lunar New Year decorations and a pinned-up loose- leaf paper asking: “Who’s your celebrity crush?”

But students had also posted stickers and slogans supporting the Palestinian cause and naming the war in Gaza as a genocide. “Zionism is terrorism,” one student’s door sticker said.

Concerned that some students might feel intimidated by such messages, the Barnard administration has decided to enforce a ban on dorm door decorations altogether. Their removal was set to begin on Thursday, and all but “official items placed by the college” will be taken down, Leslie Grinage, the dean of the college, wrote in an email to students.

“While many decorations and fixtures on doors serve as a means of helpful communication amongst peers, we are also aware that some may have the unintended effect of isolating those who have different views and beliefs,” she wrote.

Barnard has made a series of moves to limit the spaces where students and faculty can express themselves publicly since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in October. The moves are crafted broadly, but they come as Barnard and other campuses face controversy and litigation over pro-Palestinian speech that some believe is antisemitic.

The policy changes have prompted a particularly strong response at Barnard, a women’s college with a reputation as a progressive institution that values activism.

Administrators have said they are seeking to uphold free speech protections “while also ensuring that we promote a safe, respectful and inclusive campus environment,” Kelli Murray, the college’s chief administrative officer, wrote in describing new protest protocols last week.

In November, Barnard tightened editorial control over academic department websites after one department posted a message of solidarity with Palestinians. The New York Civil Liberties Union has sent a letter to the school warning that the move infringed on academic freedom.

Last week, the college set detailed restrictions for campus protests. Demonstrations are allowed on one campus lawn, Futter Field, between the hours of 2 and 6 p.m., Monday through Friday. Applications for demonstrations must be submitted 48 hours ahead of time. No amplification devices or “sound machines” — including pots, pans and musical instruments — are permitted.

The protest policies are meant to protect “opportunity for free expression while ensuring that our campus can continue to be a place of learning and living,” Jennifer Fondiller, Barnard’s vice president for communications,

said in a statement on Thursday. She said the door policy was meant to remind students of “existing housing rules so that all students feel safe and comfortable where they live.”

Columbia University, which Barnard is affiliated with, also announced a new demonstration policy. Protests on Columbia’s campus can now happen from 12 to 6 p.m. on weekdays in several designated “demonstration areas.”

Barnard administrators argue that the new protest rules are actually less restrictive than a previous rule that required 28 days’ notice. Still, some faculty have been growing increasingly alarmed. A faculty meeting last week at Barnard was dominated by pushback against the new rules, which some professors said seemed intended to suck the energy out of protests.

“Did Rosa Parks ask if it was the right time to sit in the wrong seat?” said Nara Milanich, a Barnard history professor who is critical of the changes. “I mean, it’s just maddening.”

Maryam Iqbal, a first-year student and pro-Palestinian organizer, said that despite the new rule, she did not plan to remove her door art. In fact, she has added more pro-Palestinian stickers, as well as emblems accusing the college of censoring free speech, and is waiting to see what happens.

On Thursday, the college slipped a note under her door reminding her to remove the adornments or apply for an exemption. That night, someone tore down one of her signs — the one directly critical of Barnard’s president, Laura Rosenbury — but left the others.

“I don’t understand the idea of just taking down dorm décor because it’s going to isolate someone with a different view,” she said. “That’s not how academia works.”

The union that represents the school’s residential advisers, who live in the dorms, wrote a letter to Ms. Grinage on Wednesday saying they “vehemently oppose” the new door decoration policy.

“Taking away this freedom will continue to diminish the already faltering trust students have in the current Barnard administration,” the advisers wrote.

Like other college presidents, Ms. Rosenbury, who started in the role last summer, is facing intense pressure to rein in pro-Palestinian expression. Last week, a group of Jewish students filed a lawsuit against Barnard and Columbia in federal court claiming that a tolerance of antisemitism and anti-Zionism had created “a severely hostile environment for its Jewish and Israeli students.”

They argued that the climate at the schools infringed on their civil rights by interfering with their right to an education. “Anti-Zionism is not merely a political movement — although many try to disguise it as such — but is a direct attack against Israel as a Jewish collectivity,” the lawsuit said.

Like their peer schools, Columbia and Barnard are also facing a congressional investigation into antisemitism on campus and must produce thousands of documents regarding their responses to the inquiry. A congressional hearing in December led to the resignations of the presidents of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard after they hedged in response to questions about whether they would discipline students if they called for the genocide of Jews.

Barnard students have held one pro-Palestinian protest on campus since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas war, although some students have marched in outside demonstrations. Kirsten Luce for The New York Times

Barnard has also sought to exert more control over faculty-sponsored events, several professors said. It took Debbie Becher, a sociology professor, months to get the official go-ahead to show “Israelism,” a film about Jewish disenchantment with Zionism that has become a political lightning rod. She said she didn’t get the final decision until the last minute.

“It’s as if the administration thinks that it can choreograph all of the activity that happens that might cause some kind of problem to them,” she said, “And by problem, I mean someone complaining.”

Unlike at Columbia across Broadway, where protests and counterprotests about the Israel-Hamas war are common, only one large pro-Palestinian demonstration has been held specifically at Barnard since the start of the war. About 20 students of the many more who attended the Dec. 11 protest were called into disciplinary proceedings afterward for attending an unauthorized protest, The Columbia Spectator reported.

Some received warnings; others were told the proceedings were purely informational and were dismissed. Most were students of color, raising concerns about unequal enforcement, faculty and students who attended the hearings said.

The new restrictions have made some pro-Palestinian students reluctant to demonstrate on campus.

“It has been really disheartening,” said Anagha Ram, a third-year computer science major sitting outside Milbank Hall on Wednesday, of the restrictions in general. It seemed, she said, that “they care more about financial support and donations and money and all that than their students.”

Pro-Palestinian student groups are now urging boycotts of official college events. The Barnard Bulletin on Wednesday posted a video of what it called a new form of protest: graffiti on bathroom walls reading “The students will not be silenced” and “Free Palestine.”

For several years, Izzy Lapidus, a senior, has worked for admissions, making social media videos about how much she loves Barnard. Now, she said, “I have cried many times over what Barnard has become.”

She was among the students who was called in to an inquiry meeting after attending the December protest, and was upset by how the meetings seemed designed to scare students.

“So many things have really gone directly against what Barnard’s mission statement purports to be and what this school prides itself on being,” she said.

Liset Cruz contributed reporting.