Following Hamas’s October 7th attack and Israel’s invasion, Mosab Abu Toha fled his home with his wife and three children. Then I.D.F. soldiers took him into custody.

When the war comes to Gaza, my wife and I do not want to leave. We want to be with our parents and brothers and sisters, and we know that to leave Gaza is to leave them. Even when the border with Egypt opens to people with foreign passports, like our three-year-old son, Mostafa, we stay. Our apartment in Beit Lahia, in northern Gaza, is on the third floor. My brothers live above and below us, and my parents live on the ground floor. My father cares for chickens and rabbits in the garden. I have a library filled with books that I love.

Then Israel drops flyers on our neighborhood, warning us to evacuate, and we crowd into a borrowed two-bedroom apartment in the Jabalia refugee camp. Soon, we learn that a bomb has destroyed our house. Air strikes also rain down on the camp, killing dozens of people within a hundred metres of our door. Over time, our parents stop telling us to stay.

When our apartment in the refugee camp is no longer a refuge, we move again, to a United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) school. My wife, Maram, sleeps in a classroom with dozens of women and children. I sleep outside, with the men, exposed to the dew. Once, I hear a piece of shrapnel ring through the school, as though a teacup has fallen off a table.

Now, when Maram and I talk about leaving, we understand that the decision is not only about us. It is about our three children. In Gaza, a child is not really a child. Our eight-year-old son, Yazzan, has been talking about fetching his toys from the ruins of our house. He should be learning how to draw, how to play soccer, how to take a family photo. Instead, he is learning how to hide when bombs fall.

On November 4th, our names appear on an approved list of travellers at the Rafah border crossing, clearing us to leave Gaza. The next day, we set out on foot, joining a wave of Palestinians making the thirty-kilometre journey south. Those who can travel faster than us, on donkeys and tuk-tuks, soon come into view again, travelling toward us. We see a friend, who tells us that Israeli forces have set up a checkpoint on Salah al-Din Road, the north-south highway that is supposed to provide safe passage. He says that gunfire there convinced him to turn around. We return to the school.

Mostafa and Yaffa, our six-year-old daughter, are so sick with fever that they can barely walk. My sisters have also been asking us not to go. “Let’s not leave them,” Maram says. We want to stay for our family, and we want to leave for our family.

Then, on November 15th, I am on the third floor of the school, about to sip some tea, when I hear a blast followed by screams. A type of shell that we call a smoke bomb has gone off outside. People are trying to put out a fire by dousing it with sand.

Moments later, another smoke bomb explodes in the sky above us, spewing a white cloud of gas. We race inside, coughing, and shut the doors and windows. Maram hands out pieces of wet cloth and we hold them to our noses and mouths, trying to breathe.

That night, we hear bombs and tank shells, and I barely sleep. In the days that follow, my throat tastes of gas and I have diarrhea. I cannot find a clean toilet. There is no water to flush. I feel like vomiting.

I have been joking with my family that by my thirty-first birthday, on November 17th, we will have peace. When the day arrives, I am embarrassed. I ask my mother, “Where is my cake?” She says she will bake one when she moves back into our destroyed house.

On November 18th, Israeli tank shells wreck two classrooms at another school, where Maram’s grandparents and paternal uncles are staying. My brother-in-law Ahmad learns that several members of his extended family are dead. My parents urge us not to leave our shelter. But, when we hear the news, we pretend to go to the bathroom and go looking for our relatives.

On the dusty road that leads to the school, a heartbreaking scene greets us. People are fleeing with gas cannisters, mattresses, and blankets. A group of donkeys and horses are bleeding. One horse’s tail is nearly detached. When a young man tries to quench its thirst, the water dribbles out of a hole in its neck. He asks me whether I have a knife, to put it out of its misery.

We are relieved to find Maram’s grandparents inside, sitting on the floor. As her uncles pack their things, one of them talks about fleeing to the south. Maram’s grandparents are pleading with him not to go.

The next morning, I wake at five to an overcast sky. A storm is coming. While everyone is sleeping, I fill a bottle of water from an open bucket, wash, and pray the dawn prayer. Then, at around 6:30 A.M., Maram’s uncle Nader comes to our room. He is preparing to leave for the south with his brothers. “If anyone wants to join, we will be at the gate of the hospital,” he says.

This time, when I ask Maram whether she wants to go, she says yes. “All our bags are packed,” she tells me.

Maram informs her parents of our decision. They cry as she hugs them. Then we both go to the third floor, where my parents are sitting in the corridor on a mattress. They are drinking their morning coffee with two of my sisters and their husbands. I squat, and in a low voice I tell my parents that we are going to try to leave Gaza.

My mother goes pale. She looks at my children, tears in her eyes.

I don’t want to hug anyone, because I don’t want to believe that I am leaving them. I kiss my parents and shake hands with my siblings, as though I am only going on a short trip. What I am feeling is not guilt but a sense of unfairness. Why can I leave and they cannot? We are lucky that Mostafa was born in the U.S. Does it make them less human, less worthy of protection, that their children were not? I think about how, when we go, I may not be able to call them, or even find out whether they are alive or dead. Every step we take will take us away from them.

Before Maram was my wife, she was my neighbor. In 2000, when I was eight, my father moved us out of my birthplace, Al-Shati refugee camp, and built us the house in Beit Lahia. Maram, a year younger than me, lived next door. I liked her enough that, each school year, I gave her my old textbooks so she wouldn’t have to buy new ones.

One day, Maram saw me on the third floor of our family home, peering into the distance through a new pair of binoculars. From our window, I could see the border with Israel. She sent her younger sister to ask me whether I was looking for a girl.

I told Maram’s sister that it was none of her business. After that, though, I knew Maram had feelings for me. We started to smuggle one another messages via our little sisters. In 2015, when I was twenty-two, we married.

On the morning that we set out for the south, Maram wears a jilbab and carries Yaffa’s blanket, which has the head of a fox and two sleeves, so she can wear it like a cape. We have one litre of water. By the time we gather our things and walk to the hospital gate with Maram’s youngest brother, Ibrahim, her uncles have already left.

I hail a teen-ager who is driving a donkey cart. “Going south?”

He has no idea which way is south. “How much will you pay me?” he asks.

I offer a hundred Israeli shekels, about twenty-seven U.S. dollars. Another young man, whose mother uses a wheelchair, splits the cost with us.

Our donkey cart rolls past bombed-out houses and shops. The street is a river of people flowing south, many of them carrying white flags to identify themselves as civilians. Ibrahim jumps off the donkey cart, picks up a stick, and ties a white undershirt to it.

In the crowd, I see a man named Rami, who played soccer with me more than a decade ago. He cries out with joy and asks whether his seventy-year-old father can climb into our cart. We make some space and ride on.

About thirteen kilometres into our journey, we pass Al-Kuwait Square. An Israeli checkpoint looms in the distance. Soldiers are controlling the flow of foot traffic with a tank and a sand barrier. When the soldiers want to block the way, they roll the tank onto the road.

Hundreds of people, young and old, crowd the road in front of the tank. I can think of one other scene like this—the Nakba of 1948, when Zionist militias forced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to leave their villages and towns. In photographs from that time, families flee on foot, balancing what remains of their belongings on their heads.

The children are scared. Mostafa asks me if he can go back north again to his grandmother Iman, who used to tuck him into bed. I don’t know what to tell him. We are going to see her, I finally say. Be patient.

As we near the tank, I hold up our stack of travel documents, with Mostafa’s blue American passport on top. One of the soldiers in the tank is shouting into a megaphone; another holds a machine gun. I have lived in Gaza for almost all my life, and these are the first Israeli soldiers I have seen. I am not afraid of them, but I will be soon.

We are overjoyed to spot, up ahead of us, Maram’s uncles. Ibrahim shouts out. One of them, Amjad, grins and yells back, “You made it!”

The line crawls along. One of Maram’s great-uncles, Fayez, is pushing a wheelchair carrying Maram’s ninety-year-old great-grandmother. To my surprise, Fayez convinces the soldiers that elders should go through first, with one person to accompany them. But, when two people try to accompany one wheelchair, a soldier angrily orders them to stop. He fires his gun into the ground.

Children scream. Panic ripples through the line. A gust of wind blows, as if to rearrange the stage of the theatre. The tank rolls back onto the road, and about twenty minutes elapse before it backs up again.

We are about to pass the checkpoint when a soldier starts to call out, seemingly at random.

“The young man with the blue plastic bag and the yellow jacket, put everything down and come here.”

“The man with white hair and a boy in his arms, leave everything and come!”

They’re not going to pull me out of the line, I think. I am holding Mostafa and flashing his American passport. Then the soldier says, “The young man with the black backpack who is carrying a red-haired boy. Put the boy down and come my way.” He is talking to me.

I make the sudden decision to try to show the soldiers our passports. Maram keeps my phone and her passport. “I will tell them about us, that we are going to the Rafah border crossing and that our son is an American citizen,” I say. But I have taken only a few steps when a soldier orders me to freeze. I am so scared that I forget to look back at Mostafa. I can hear him crying.

I join a long queue of young men on their knees. A soldier is ordering two elderly women, who seem to be waiting for men who have been detained, to keep walking. “If you don’t move, we will shoot you,” the soldier says. Behind me, a young man is sobbing. “Why have they picked me? I’m a farmer,” he says. Don’t worry, I tell him. They will question and then release us.

After half an hour, I hear my full name, twice: “Mosab Mostafa Hasan Abu Toha.” I’m puzzled. I didn’t show anyone my I.D. when I was pulled out of line. How do they know my name?

I walk toward an Israeli jeep. The barrel of a gun points at me. When I am asked for my I.D. number, I recite it as loud as I can.

“O.K., sit next to the others.”

About ten of us are now kneeling in the sand. I can see piles of money, cigarettes, mobile phones, watches, and wallets. I recognize a man from my neighborhood, who is slightly younger than my father. “The most important thing is that they don’t take us as human shields for their tanks,” he says. This possibility never crossed my mind, and my terror grows.

We are led, two by two, to a clearing near a wall. A soldier with a megaphone tells us to undress; two others point guns at us. I strip down to my boxer shorts, and so does the young man next to me.

The soldier orders us to continue. We look at each other, shocked. I think I see movement from one of the armed soldiers, and fear for my life. We take off our boxer shorts.

“Turn around!”

This is the first time in my life that strangers have looked at me naked. They speak in Hebrew and seem cheerful. Are they joking about the hair on my body? Maybe they can see the scars where shrapnel sliced into my forehead and neck when I was sixteen. A soldier asks about my travel documents. “These are our passports,” I say, shivering. “We are heading to the Rafah border crossing.”

“Shut up, you son of a bitch.”

I am allowed to put on my clothes, but not my jacket. They take my wallet and tie my hands behind my back with plastic handcuffs. One of the soldiers comments on my UNRWA employee card. “I’m a teacher,” I tell him. He curses at me again.

The soldiers blindfold me and attach a numbered bracelet to one wrist. I wonder how Israelis would feel if they were known by a number. Then someone grabs the back of my neck and shoves me forward, as though we are sheep on our way to be slaughtered. I keep asking for someone to talk to, but no one responds. The earth is muddy and cold and strewn with rubble.

I am pushed onto my knees, and then made to stand, and then ordered to kneel again. Soldiers keep asking in Arabic, “What’s your name? What’s your I.D. number?”

A man addresses me in English. “You are an activist. With Hamas, right?”

“Me? I swear, no. I stopped going to the mosque in 2010, when I started attending university. I spent the last four years in the United States and earned my M.F.A. in creative writing from Syracuse University.”

He seems surprised.

“Some Hamas members we arrested admitted you are a Hamas member.”

“They are lying.” I ask for proof.

He slaps me across the face. “You get me proof that you are not Hamas!”

Everything around me is dark and frightening. I ask myself, How can a person get proof of something that he is not? Then I am walked aggressively forward again. What did I do? Where will they take us?

I am told to remove my shoes, and a group of us are led somewhere else. Cold rain and wind strike our backs.

“You raped our girls,” someone says. “You killed our kids.” He slaps our necks and kicks our backs with heavy boots. In the distance, we can hear artillery fire slicing through the air.

One by one, we are forced into a truck. Someone who is not moving lands on my lap. I fear that a soldier has thrown a corpse onto me, as a form of torture, but I am scared to speak. I whisper, “Are you alive?”

“Yes, man,” the person says, and I sigh with relief.

When the truck stops, we hear what sound like gunshots. I no longer feel my body. The soldiers give off a smell that reminds me of coffins. I find myself wishing that a heart attack would kill me.

At our next stop, we kneel outside again. I start to wonder whether the Israeli military is showing us off. When a young man next to me cries, “No Hamas, no Hamas!,” I hear kicks until he falls silent.

Another man, maybe talking to himself, says quietly, “I need to be with my daughter and pregnant wife. Please.”

My eyes fill with tears. I imagine Maram and our kids on the other side of the checkpoint. They don’t have blankets or even enough clothes. I can hear female soldiers, chatting and laughing.

Suddenly, someone kicks me in the stomach. I fly back and hit the ground, breathless. I cry out in Arabic for my mother.

I am forced back onto my knees. There is no time to feel scared. A boot kicks me in the nose and mouth. I feel that I am almost finished, but the nightmare is not over.

Back in the truck, my body hurts so much that I wish I had no hands or shoulders. After what feels like ninety minutes of driving, we are taken off the truck and shoved down some stairs. A soldier cuts my plastic handcuffs. “Both hands on the fence,” he says.

This time, the soldier ties my hands in the front. A sigh of relief. I am escorted about fifteen metres. Finally, someone speaks to me in what sounds like native Palestinian Arabic. He seems to be my father’s age.

At first, I hate this man. I think he is a collaborator. But later I hear him described as a shawish—a detainee like us, with little choice but to work for his jailers. “Let me help you,” he says.

The shawish dresses me in new clothes and walks me inside the fence. When I raise my blindfolded head, I get blurry glimpses of a corrugated metal roof. We are in some kind of detention center; soldiers walk around, watching us. The shawish unrolls what looks like a yoga mat and covers me with a thin blanket. I place my bound hands behind my head, as a pillow. My arms sear with pain, but my body slowly warms. This is the end of day one.

For years, I have dreamed of looking out the window of a plane and seeing my home from above. In my adult life, I have never seen a civilian flight over Gaza. I have seen only warplanes and drones. Israel bombed Gaza’s international airport in the early two-thousands, during the second intifada, and it has not operated since.

Most of my friends have never left Gaza. But in recent years, as they have struggled to find jobs and feed families, they have asked, How long should I wait? Some have immigrated to Turkey, and then to Europe. Some envy my three trips to the U.S. Each time I have returned, with photos of unfamiliar cities and trees and snow, people have called me “the American,” and asked me why I came back. There is nothing in Gaza, they say. I always tell them that I want to be with my family and my neighbors. I have my house and my teaching job and my books. I can play soccer with my friends and go out to eat. Why would I leave Gaza?

We wake to the sound of a soldier shouting into a megaphone. The shawish makes sure everyone is kneeling on the floor. He has told us that we are in a place called Be’er Sheva, in the Negev Desert. This is my first time in Israel.

The youngest of us, whose voice I recognize from the line, suddenly screams out that he is innocent. “I need to see my mother,” he says. My feet start to feel numb.

I hear shouting and beating. “O.K., O.K., I will shut up,” he says. “But please send me back.” More beating follows.

The person next to me asks the shawish for water. “No water yet,” the shawish says. He sounds frustrated, and I sympathize with him. More than a hundred detainees depend on him. When he takes me to the toilet, for the first time since the previous morning, he has to help me open the door and position me to urinate. The stench is very strong.

Breakfast is a small piece of bread, some yogurt, and a slosh of water poured directly into our mouths. I am not hungry, not even for my mother’s birthday cake. When I return to the toilet, around noon, the shawish tells me that there is no toilet paper or water to wash myself.

Later, a soldier tells the shawish that we will be going to see a doctor. I sense relief in the room.

“I will tell him about my diabetes.”

“Yes, and I will tell him about my bladder problem.”

I will tell him about the pain in my nose, upper jaw, and right ear, where I had surgery a few years ago. Since I was kicked in the face, my hearing is weaker than before.

We kneel outside, with our hands on the back of the person in front of us. Wind strikes us; stones dig into our knees. We are put in a bus and a soldier pushes my head down, even though I can’t see anything. Maybe they don’t want to look at our faces.

When we exit the truck and my name is called, I am temporarily given my I.D. card. I feel a prick of hope. Maybe they are going to release us.

Inside a building, my blindfold is pulled off. A soldier is aiming an M-16 at my head. Another soldier, behind a computer, asks questions and takes a photo of me. Another numbered badge is fastened to my left arm. Then I see the doctor, who asks whether I suffer from chronic diseases or feel sick. He does not seem interested in my pain.

Back at the detention center, blindfolded again, we kneel painfully for hours. I try to sleep. A man moans nearby; another is hopeful that he will get to go back to the doctor. Late in the evening, a soldier calls my name. The shawish leads me to the gate, and a jeep comes to take me away.

I am tied to a chair in a small room. An Israeli officer, Captain T., comes in and asks, “Marhaba, keefak?” This is Arabic for “Hello, how are you?”

I am very sad because of everything that has been done to me, I tell him.

Don’t be sad, he says. We will talk.

The captain leaves the room and comes back with coffee. A soldier unties my right arm, so I can hold my cup.

I will tell him everything about me, I say, including where I was on October 7th, but I want him to answer one question.

“Sure. I’m listening.”

Will he release me if there is nothing on me?

He promises that he will.

He takes notes as I tell him about my trips to the U.S., my poetry book, and my English students. I tell him that on the morning of October 7th, when Hamas began to launch rockets at Israel, I was wearing some new clothes, and my wife was taking a photo of me. The sound of rockets made Yaffa cry, so I showed her some YouTube videos on my phone. My father and brothers were on different floors of the house, and we started to shout a conversation out the windows. What’s happening? Is this some kind of test?

On Telegram, we started to find videos of Hamas fighters inside Israel with their jeeps and motorcycles, encircling houses and shooting Israeli soldiers. In the beginning, some Gazans seemed excited and happy about the attack. But many of us were perplexed and scared. Although Gaza has been devastated by the Israeli occupation, I could not justify the atrocities committed against Israeli civilians. There is no reason to kill anyone like that. I also knew Israel would respond. Hamas had never done something like this before, and I feared that Israeli retaliation would be unprecedented, too.

Captain T. asks me two questions. First, do I know of any Hamas tunnels or plans for ambushes?

I spent most of the past four years in the United States, I say. I spend my time teaching, reading, writing, and playing soccer. I don’t know these things, and I’m not involved with Hamas.

Then Captain T. asks me the names and ages of my family members. Before I leave, he tells me that he hails from a family of Moroccan Jews. There are many shared things between us, he says. I nod and smile, trying to believe that he means what he says.

I ask him what will happen to me. They will look into what I have told him, he says. It may take several days.

“And then?”

“We will either imprison or release you.”

I am on a bed, shackled and waiting to go back to the detention center. Someone comes to take me away, but then stops and has a conversation with someone else. They leave me for a while, and I fall asleep to the sound of Hebrew music. I like the singer’s voice.

When I wake, a soldier says something in English that I cannot believe.

“We are sorry about the mistake. You are going home.”

“Are you serious?”

Silence.

“I will go back to Gaza and be with my family?”

“Why wouldn’t I be serious?”

Another voice chimes in: “Isn’t this the writer?”

Back at the detention center, as I fall asleep, I think about the words “We are sorry about the mistake.” I wonder how many mistakes the Israeli Army has made, and whether they will say sorry to anyone else.

On Tuesday, about two days after I left the school, the man with the megaphone teaches us how to say good morning in Hebrew. “Boker Tov, Captain,” we say in unison. Some new detainees have arrived in an enclosure nearby, and the soldiers overseeing them seem to be having fun. They sing part of an Arabic children’s song, “Oh, my sheep!,” and order the detainees to say “Baa” in response.

About an hour later, a soldier calls out my name and orders me to stand near the gate. The shawish warns me that they might interrogate me and beat me again. “Be strong and don’t lie,” he says. I feel a surge of panic.

After an hour, some soldiers approach. One has my I.D., and another drops a pair of slippers for me and tells me to walk. Then one of them says, “Release!”

I am so overjoyed that I thank him. I think about my wife and children. I hope that my parents and siblings are alive.

I spend about two hours at the place where I was interrogated, with the Hebrew music. I am given some food and water, but the soldiers never find my family’s passports. I climb into a jeep, surrounded by soldiers. After two hours, I can see around my blindfold that we are getting close to Gaza.

The soldiers get out, smoke, and return fully armed, wearing their vests and helmets. I am thinking about the man I recognized in line, and what he said about human shields. I am starting to wish that I could go back to the detention center when they give me my I.D. card.

Standing against a wall, I tell the closest soldier that I am scared.

“Do not feel scared. You will leave soon.”

My handcuffs are cut, and the blindfold is removed. I see the place where I had to take my clothes off. When I see new detainees waiting there, sadness overwhelms me.

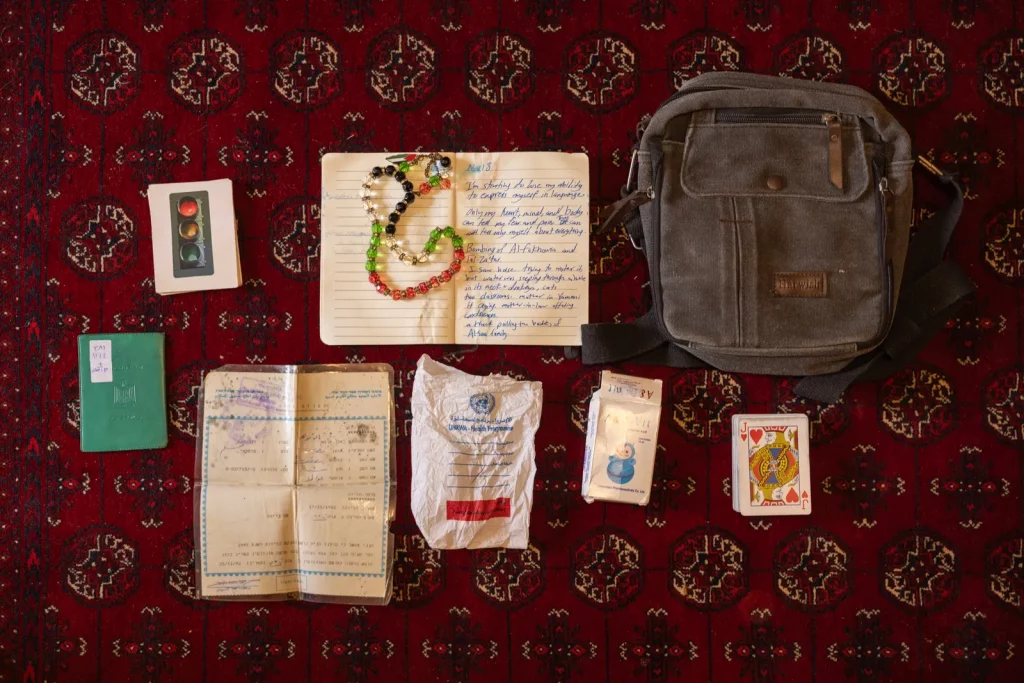

I walk fast. Back at the checkpoint, in a big pile of belongings, I find my handbag, but not Yazzan’s backpack, where we stuffed our children’s winter clothes. A soldier shouts angrily at me. “I was just released,” I say.

Back on Salah al-Din Road, dozens of people are waiting. A crying mother asks if I have seen her son. “He was kidnapped on Monday,” she says. It is Tuesday. I have not seen him.

I have no money and no phone, but a kind driver offers to drop me off in the southern city of Deir al-Balah. I know that my wife’s relatives have taken refuge there, and Maram probably would have joined them with the kids. As the man drives, I keep asking where we are, and he recites the names of refugee camps: Al-Nuseirat, Al-Bureij, Al-Maghazi.

In Deir al-Balah, I ask some young people, who are standing outside a bank, using its Wi-Fi, whether they know anyone from my home town. One of them points me toward a school.

I take off my slippers and start to run. Passersby are staring, but I don’t care. Suddenly, I spot an old friend, Mahdi, who once was the goalkeeper on my soccer team. “Mahdi! I’m lost—help me.”

“Mosab!” We hug each other.

“Your wife and kids are at the school next to the college,” he says. “Just turn left and walk for about two hundred metres.”

I cry as I run. Just when I start to worry that I have lost my way, I hear Yaffa’s voice. “Daddy!” She is the first piece of my puzzle. She seems healthy, and is eating an orange. When I ask where the rest of the family is, she takes my hand and pulls me as if I were a child.

Maram’s uncle Sari rushes off to find Maram. He does not tell her that I have arrived, only that she should return to the school for dinner. When she sees me, she looks like she might collapse, and I run toward her.

I learn from Maram how lucky I was. She used my phone to inform friends around the world, who demanded my safe release. I think about the hundreds or thousands of Palestinians, many of them likely more talented than me, who were taken from the checkpoint. Their friends could not help them.

The next day, Wednesday, I go to the hospital to have my injuries examined and see patients and corpses everywhere—in the corridors, on the steps, on desks. I manage to get an X-ray, but there are no results: the doctor’s computer isn’t working. I leave with a prescription for painkillers.

That Friday, a temporary ceasefire begins. Two of my wife’s uncles try to go north, only to return an hour later. They say that Israeli snipers have shot and killed two people. At the souk, clothing costs more than ever. I wait five hours at an UNRWA aid center in the hope of receiving some flour, without success. A line to refill gas cannisters seems about a kilometre long.

As soon as the ceasefire ends, about seven hundred Palestinians are killed in twenty-four hours. Until recently, the south has been comparatively safe, but now we hear bombs not far away.

Then the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem calls, advising us to head to the Rafah border crossing.

I struggle to find us a ride. The journey is about twenty kilometres, and the first two drivers we ask are scared. Israeli forces have isolated Rafah from the nearby city of Khan Younis. After a few calls, Maram’s cousin, a taxi-driver, agrees to take us.

At the crossing, we wait with hundreds of Gazans for four hours. I have my I.D., which lists my children’s names, but only Maram has her passport. I worry that we don’t have the right documents to get through the crossing. But, at 7 P.M., officials wave us through the gate, and we join a crowd of exhausted families in the Egyptian travellers’ hall. I feel as though I have been cured. The American Embassy gives us an emergency passport for Mostafa, and the Palestinian Embassy gives us single-use travel documents. Then a minibus takes us to Cairo.

In “A State of Siege,” the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish writes something that is difficult to translate. “We do what jobless people do,” he says. “We raise hope.” The verb nurabi, meaning to raise or to rear, is what a parent does for a child, or what a farmer does for crops. “Hope” is a difficult word for Palestinians. It is not something that others give us but something that we must cultivate and care for on our own. We have to help hope grow.

I hope that when the war ends I can go back to Gaza, to help rebuild my family home and fill it with books. That one day all Israelis can see us as their equals—as people who need to live on our own land, in safety and prosperity, and build a future. That my dream of seeing Gaza from a plane can become a reality, and that my home can grow many more dreams. It’s true that there are many things to criticize Palestinians for. We are divided. We suffer from corruption. Many of our leaders do not represent us. Some people are violent. But, in the end, we Palestinians share at least one thing with Israelis. We must have our own country—or live together in one country, in which Palestinians have full and equal rights. We should have our own airport and seaport and economy—what any other country has.

An Egyptian friend welcomes us to Cairo. She lives in the Zamalek neighborhood, on an island in the Nile. When I visit her garden, I see flowers that my parents grew in Beit Lahia. On her shelves, I see books that I left behind, under the rubble. When I tell her that her house reminds me of home, she begins to cry.

Later, I find an article in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz about a detention center in Be’er Sheva. It describes the same conditions that I experienced, and says that several detainees have died in Israeli custody. When the Israeli Army is reached for comment about my story, a spokesperson says, “Detainees are treated in line with international standards, including necessary checks for concealed weapons. The IDF prioritizes detainee dignity and will review any deviations from protocols.” The spokesperson does not comment on detainee deaths.

On Telegram, I find a video of Khalifa Bin Zayed Elementary, an UNRWA school that Yazzan, Yaffa, and I all attended. Two of Maram’s uncles, Naseem and Ramadan, who were born deaf and mute, have been sheltering there with their families. When the kids hear the video, they drop their toys and join me. “There is my classroom,” Yaffa says. She started first grade a few weeks ago. Yazzan sees his classroom, too. In the video, the school is on fire.

I learn from a relative that the men in the school were taken to a hospital, stripped, and interrogated by Israeli forces. Afterward, Naseem and Ramadan went looking for their children. My relative says that, near the entrance to the school, a sniper shot them both, killing Naseem.

Naseem’s younger brother Sari, whom I saw only days ago, sends me a photo of Naseem, wearing a white doctor’s uniform stained with his blood. “These were the only clothes they could find at the hospital,” Sari tells me on WhatsApp. Maram sits next to me, weeping.

The next day, Maram is cooking maqluba, a dish of rice, meat, and vegetables, which I have not eaten for two months. I am savoring the smell of potatoes and tomatoes when I get a call from a private number.

“Hello, Mosab. How are you?”

It is my father-in-law, Jaleel. At the sound of his voice, Maram’s eyes brim with tears. He tells us that everything is fine, even though we know that this can’t possibly be true. Then her mother comes to the phone.

“I’m sorry for our loss, Mum,” Maram says. I hear her mother sob.

“Mum, are you taking your medicine?”

“Don’t worry about me,” she says. We never stop worrying about them.

I do not know whether our journey will end in Egypt or continue to the United States. I only know that my children need to have a childhood. They need to travel, and be educated, and live a life that is different from mine.

I have come to Egypt with only one book, a worn-out copy of my poetry collection. Since I last read it, I have lived a lot of new poems, which I still have to write. After weeks of typing on my phone, in streets and in schools, I am not used to opening my laptop without worrying about when I can charge it. I am not used to being able to close the door. But one morning I sit at my friend’s beautiful wooden desk, in a room full of light, and write a poem. It is addressed to my mother. I hope that the next time we speak I can read it to her.

♦Published in the print edition of the January 1 & 8, 2024, issue, with the headline “Unsafe Passage.”