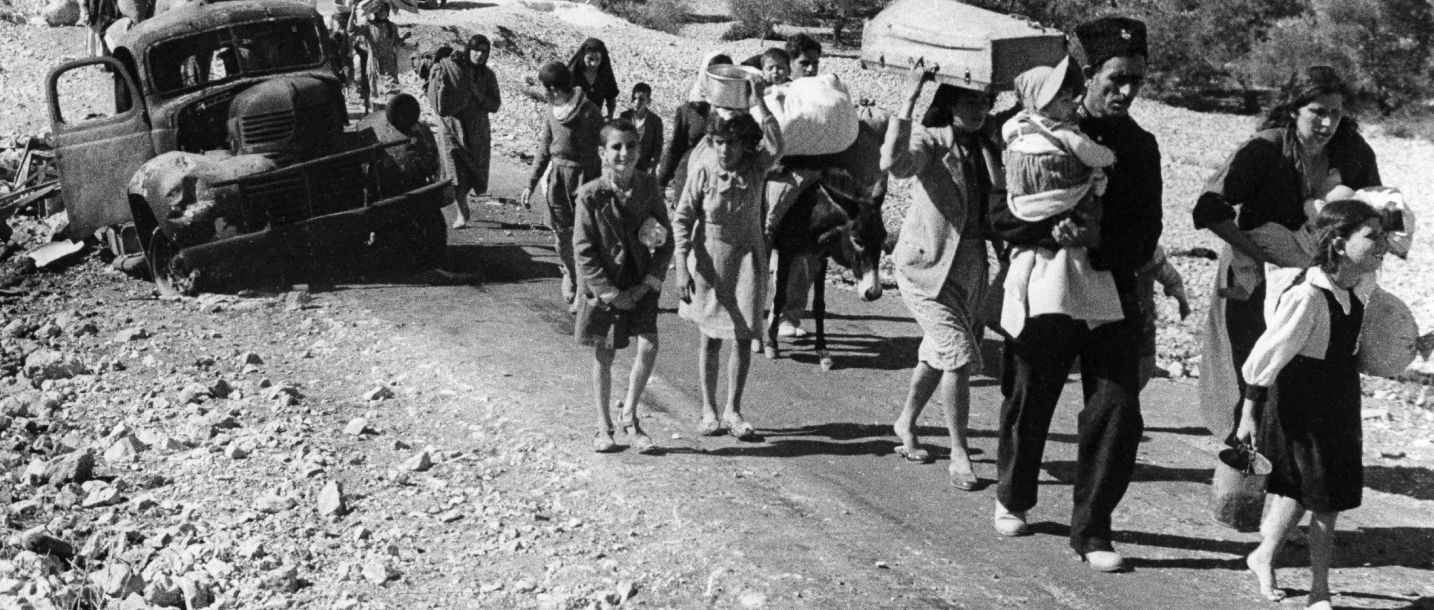

Historian Adel Manna tells the story of the 120,000 Palestinians who remained in Israel in 1948 while 750,000 were driven out

When he was in the fourth grade in elementary school in the Arab town of Majd al-Krum in Upper Galilee, Adel Manna took part in the preparations to celebrate Israel’s 10th Independence Day. At home, he told his father, Hussein, about how thrilled he was to be in a play about the achievements of the Zionist movement and the young state. His father’s face clouded over. Sitting Adel, his firstborn child, by his side, he explained with much forbearance why the event was not a cause for celebration for the Arabs, rather a day of grief and trauma. “It is not a day of istiqlal [independence] but of istakhlal [conquest, occupation],” he said.

“My father told me about the murders that Israel Defense Forces soldiers committed in Majd al-Krum in November 1948, and that months after the end of the war, hundreds of residents were expelled, including our family,” Manna tells me during an interview in Jerusalem. In January 1949, his family crossed into Jordan and afterward went on to Ein al-Hilweh refugee camp in southern Lebanon.

Sixty years have passed since Manna grasped the difference between those two Arabic words. The circumstances of his family’s exile and subsequent return to the ancestral home have haunted him all his life. Now, following a difficult gestation, those experiences have produced a groundbreaking historical study, “Nakba and Survival: The Story of the Palestinians Who Remained in Haifa and the Galilee, 1948-1956,” which first came out in Arabic and has recently been published in Hebrew. The term Nakba, or “catastrophe,” is used to describe Israel’s War of Independence, when hundreds of thousands of Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes. In the Hebrew version of his book Manna uses the Hebrew word sordim for survivors, i.e., those who remained (as opposed to the term nitzolim, connoting Holocaust survivors, which he says has in essence been appropriated by the Jews).

I begin our conversation by asking Manna when he arrived at the decision that the book’s protagonists would be those who survived/remained after the events of 1948-49.

“Survival is strength,” he replies. “It is the ability to confront a disaster, such as an earthquake, and to hold on and rescue your family and property. That is what happened to the Arabs in Israel, and that disaster did not end in 1948 but went on at least until 1956. The Palestinians became a minority ruled by the Jews, with whose language and laws they were not familiar. Formally they were citizens, but effectively they were under occupation. Their rights were trampled, their property was expropriated and plundered, they could not leave their village without a permit, and so on. One needs strength, and above all strategies, to survive. I call it the strength of the defeated: not to yield to despair, and to ensure that your family remains alive. [Israeli] historian Benny Morris and others like him hate my book, because I am taking the story from them and brazenly also claiming that the Palestinians survived, even though after World War II and the Holocaust, the Jews have a monopoly on the word ‘survival.’”

Aren’t you actually replacing the [Arabic] term summud – steadfastness – with [the Hebrew] hisardut, or survival?

“In the Arabic version of the book, I use the word bakaa, which means remaining alive. The Palestinians did not face extinction in the 1948 Nakba, as I emphasize in the book. Not everyone managed to come through and rehabilitate his life; some despaired and left. Families split apart and did not see one another for years. Some Palestinians preferred to remain in the homeland under military rule and to bend in order to survive, despite their private tragedy, which was also a national and political tragedy.

“This is also a story of rebirth. The term summud is from the 1980s, and connotes a political and ideological approach: namely, I must hold fast to the land. After the West Bank Palestinians despaired of the possibility of liberating Palestine, they spoke of a commitment to cling steadfastly to the territories that were occupied in 1967.”

When did the Palestinians in Israel grasp that it was incumbent on them to survive?

“At the start of the war in 1948, many fled for their lives, believing they would soon return. But in short order they understood that central Galilee and western Galilee, which in the United Nations partition plan were supposed to be part of the Arab state, would be lost. When you realize that those who left will not be able to return, and hear that the conditions in the refugee camps in Lebanon are dire, you realize that abandonment is not an option.

“The residents of the Arab city of Nazareth and its 20 surrounding villages were not expelled in Operation Hiram [in October 1948, aimed at taking control of the Upper Galilee from the Arab Liberation Army]. When the Israel Defense Forces reached locales such as Bana, Deir al-Assad, Nahaf and others” as part of the operation, Manna continues, “the soldiers entered the villages, put the men in groups, shot a few and ordered everyone: ‘Yallah, to Lebanon!’ The villagers ostensibly left and started to walk northward. The soldiers did not go with them. Often, after going five or 10 kilometers, and without a soldier in sight, they returned and found people to liaise with the Israeli commanders. People started to develop survival skills.”

The book, then, focuses on the Palestinians who were not expelled, and Manna focuses on groups such as the Druze, who joined the IDF as early as June 1948, and others such as the Circassians and some of the Bedouin villages in Galilee. In the main, Manna deals with Nazareth and many of its surrounding villages, which emerged almost unscathed from the Nakba in the wake of an Israeli decision of July 1948. The author analyzes the circumstances that allowed about 100,000 Palestinians to remain in Galilee and Haifa, whereas another 750,000 were dislocated and fled.

Christians vs. Muslims

“In 1948,” he says, “the high-ranking political decision makers issued explicit directives to IDF officers not to harm or expel the residents of Nazareth and many villages around it. Israel’s policy in regard to the Christians was more moderate than toward Muslims. There is the well-known case of the Christian village of Ilabun, where a massacre was perpetrated and the villagers were expelled to southern Lebanon – but, in a unique instance, those refugees were allowed to return to their homes and their land. In contrast, the Muslims in Galilee were victims of ethnic cleansing.”

On what basis do you maintain that most of the deportees were Muslims?

“If we focus on Galilee, the fact is that many Christians from Acre and Haifa were also expelled. This contradicts the account of Israeli historians to the effect that Haifa mayor Shabtai Levy drew up an emotional leaflet, urging the Arab residents not to leave the city where they had lived for so many years. I interviewed Haifa residents – members of the Communist Party who are not nationalists and certainly do not hate Israel. Not one of them ever heard of that leaflet, and on the day it was supposedly distributed, the Haganah [pre-IDF paramilitary organization] shelled the Arab neighborhoods from Mount Carmel. In Haifa there was no expulsion in the sense of people being forced onto trucks at gunpoint. But when entire neighborhoods were shelled, people rushed to the port. The same pattern was repeated in Acre and Jaffa.”

Did Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion pursue a policy or issue an order aimed at getting rid of the Muslims?

“I am not looking for a directive or a document bearing Ben-Gurion’s signature. He addressed the subject often, and I quote his statements in the book. For example, on September 26, 1948, he declared, ‘Only one task remains for the Arabs in the Land of Israel: to flee.’ The Israeli leadership understood and also concurred that, for the Jewish state, the fewer Arabs the better. The subject was mooted already in the late 1930s. Yosef Weitz, a senior official of the Jewish National Fund, supported extensive expulsion of Arabs and advocated a population transfer. The IDF commanders at different levels knew what the leadership wanted and acted accordingly. Massacres were not perpetrated everywhere. When you shell a village or a city neighborhood, the residents flee. In the first half of 1948, at least, they believed they would be able to return. When the fighting in Haifa ended, many residents tried to return from Acre in boats, but the Haganah blocked them.”

Does your study confirm, or prove, that ethnic cleansing took place?

“The book’s goal is not to prove whether ethnic cleansing occurred. My disagreement with [the review of my book in Haaretz by] Benny Morris did not revolve around the question of ‘whether ethnic cleansing took place or not,’ but deals with the question of whether the leadership did or did not make a decision in a particular meeting to implement a policy of ethnic cleansing.” In this connection, Manna quotes Daniel Blatman’s response (Haaretz, Aug. 4) to a review of his book by Morris (Haaretz, July 29). One might think from Morris’ book, Blatman noted, that “when Ratko Mladic decided to slaughter over 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica in 1995, he made his orders public.”

Indeed, Manna points out, “The first historian who uncovered the fact that ethnic cleansing occurred and that there were also cases of massacre, rape and expulsion was Benny Morris. He reached the conclusion that there was no [official] policy, in light of the fact that no authoritative archival documentation exists. In one village, they decided a certain way and in another, differently. Still, there is a pattern: The soldiers perpetrated another massacre and carried out another expulsion, and another massacre and another expulsion, and no one was brought to trial. If there was no policy, why weren’t these war criminals tried?”

A case in point: the atrocities that were carried out in the village of Safsaf, northwest of Safed, on October 30, 1948, which included murder, expulsion and rape. Manna writes that a member of his wife’s family was raped and murdered in cold blood by IDF soldiers: His wife, Aziza, is named for the rape victim. He heard the account nine years ago from a woman named Maryam Halihal, now 80, who was 10 at the time of the events.

Rape is considered a dishonoring of the family in Arab society. Did you have qualms about publishing the story and the identity of the victims?

“Rape generates deep shame in the victim’s family. Aziza Sharaida is no longer alive – why make her harsh story public and shame her family? When I met the woman who would become my wife, she told me that she was named for a cousin, Aziza Sharaida, without elaborating. As part of my research, I interviewed members of my wife’s family, and Maryam Halihal decided to talk about the incident, over her husband’s angry objections.

“The soldiers entered the family’s house and tried to rape Aziza Sharaida in front of her husband and children. She resisted. The soldiers threatened to kill her 17-year-old, firstborn son if she went on resisting. She resisted with force and they shot her son. The soldiers threatened to shoot her husband, too, but she refused to give in, and they shot and killed him. The two younger sons, who witnessed the atrocity, went into exile in Lebanon. My wife’s mother, a relative of the murdered woman, decided 63 years ago to name her daughter Aziza. As I write in the book, even though Haim Laskov [later a chief of staff] was put in charge of the interrogation of the perpetrators of the horrors in Safsaf, none of them paid the price for war crimes, which included shooting prisoners and acts of abuse and rape.”

Manna began his research in 1984. Over the years, he interviewed 120 men and women and compiled documents, diaries and letters from the period, which in some cases had been stashed away in drawers. He also drew on written Palestinian sources, which helped him confirm oral testimonies. Memoirs published in Arabic and newspaper articles form the period, in Arabic and Hebrew, contributed to the research. Manna also made use of many studies by Jewish Israeli historians. However, he says, he did not resort to the sweeping preference for Israeli archives that characterizes such historians as Benny Morris. “The blatant manner in which oral testimonies are disdained and ignored by researchers in Israel reflects a domineering attitude,” he writes in the book’s introduction.

He will not deposit the material he’s collected over the years in an Israeli archive. It will go either to Bir Zeit University, near Ramallah, or to the Beirut-based Institute for Palestine Studies. “Palestinian students can’t get to the Hebrew University [of Jerusalem],” he says.

Palestinian ‘illegals’

As a Muslim born in 1947 in Majd al-Krum and as a historian who researched the special story of his village in the 1948 war, Adel Manna decided that it was his obligation to write the history of the 120,000 Arabs who remained in Israel – the generation of his parents, Hussein and Kawthar.

“They survived the policy of a military government under which their rights were trampled, and despite that were able to raise nine children and instill in us the message that no one is entitled to treat us as inferior people,” he says.

Turning to his parents’ ordeal in the 1948 war, Manna relates, “The first person in Majd al-Krum who was blindfolded and made to stand against a wall in the village square – before being shot to death by a squad of six soldiers – was the husband of my grandmother, Zahra,” he explains. Subsequently, “In January 1949, 536 residents were expelled, including members of her family and her children, and became refugees in Lebanon. Her brother was murdered by a resident of [the Jewish community of] Pardes Hannah; her son, Samih, was killed when he stepped on a land mine. After the war, she worked as a maid in Haifa with her daughter. For two years, my father ‘infiltrated’ into Israel to visit them and take back a little money that grandmother had saved up for him and for his brother in Lebanon.”

Manna was a year old when he and his parents were among the many from Majd al-Krum who were herded onto IDF trucks that took them west to the village of Al-Birwa (today, the location of Moshav Ahihud), then south toward the Jezreel Valley and Wadi Ara.

“The trucks stopped there,” he relates. “The people were ordered to get off amid shouts of ‘Yallah, go to King Abdullah’ [in Jordan]. My parents spent one night in a mosque in Kafr Ara and from there walked to Nablus [then part of Jordan]. We spent the hard winter of 1949 there. People were crowded into tents under grim hygienic conditions. In April, the Jordanians encouraged the refugees to leave. My parents decided to go north and reached Ein al-Hilweh [in Lebanon]. I almost died in the refugee camp, like other infants.”

Due to an intestinal ailment, Manna did not stand or walk until he was 2 and a half. “A woman in the camp deduced that this was why I couldn’t stand and made me a potion from herbs and castor oil. It eradicated the parasites, and within a day or two I was walking. We returned to Israel in 1951 in a fishing boat that set out from the port of Tyre in Lebanon and brought us, the Palestinian ‘illegals,’ to the beach of Shavei Tzion [returners to Zion], north of Acre. How symbolic,” Manna says with a smile.

How did you manage to get back?

“Like many Galilee Palestinians, my father had repeatedly ‘infiltrated’ into Israel. On one such occasion he learned that a lawyer, Hana Naqara, had petitioned the High Court of Justice on behalf of 43 Majd al-Krum residents, each of whom had returned to the village more than once but had been expelled back to Lebanon each time. Naqara argued that these people had [Israeli] ID numbers – a population census had been conducted in Majd al-Krum in December 1948, the month before they were originally deported. [Those who received an official ID number were considered citizens.] Like them, my parents also had ID numbers. Back in Lebanon, my father told my mother: ‘Prepare what’s needed – tonight we’re going back to the village.’

“My mother was seven months pregnant, how was she going to walk 40 kilometers? Father told her that a Palestinian fisherman from the village of Az-Zeeb [Hebrew name: Achziv] had discovered that transporting refugees by boat was more profitable than fishing. As a child I believed that my father was a great hero, who had thought up the idea of our return by boat. While researching the book I learned that many Galileans had returned to Israel via the sea – a subject that awaits historical research.”

‘Don’t be a donkey’

“Nakba and Survival” is dedicated to the memory of Manna’s father. His mother, Kawthar (“pure water”), 89, lives in the family home in the village, and contributed considerably to the book.

Manna recalls that the first Jews he met as a boy were women. At the time, he traveled to the Haifa suburbs of Kiryat Motzkin and Kiryat Bialik to sell figs from the family grove. There he discovered not only that the Jews lived in apartment buildings and that shade trees had been planted along the road, but also that Jewish women were very affable. One of them, Mrs. Miller by name, treated him warmly, and when police officers showed up to confiscate wares of Arab peddlers, she hid his baskets of figs in her home.

Adel remembers his father telling him, “Don’t be a donkey like me, who works as a manual laborer all his life from morning to evening and has a hard time providing for his nine children. Get an education, so you can get a job with a good salary.”

Manna obtained a B.A. in history from the University of Haifa, then his master’s and doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, writing his dissertation on the history of the Jerusalem district in the Ottoman period. His adviser, Gabriel Baer, advised him to steer clear of issues such as the Nakba and the conflict, he recalls: “Prof. Baer intimated that the topics I had in mind would not help a student like me forge an academic career. In retrospect, I appreciated his advice.”

Manna’s political awareness was honed in the 1970s, when he was a student in Haifa, living in the dorms. He was elected secretary of the Arab Students Union, whose activity included organization of cultural and political events. His political activity exacted a price, he says: “I came under pressure from Shin Bet [security service] agents, who tried to recruit me as a collaborator and promised that in return I would be allowed to become a teacher. ‘What are you going to do with a B.A. in history?’ a Shin Bet agent named Carmi said to me. Instead of giving in or being afraid, I told Gideon Spiro, the editor of the student newspaper, about it.

“The newspaper published a report headlined ‘Shin Bet harassing Arab student,’ on February 2, 1972, a week before I received my degree. The article stirred a furor in the university and in the Hebrew press. In its wake, the weekly magazine Haolam Hazeh ran a follow-up article. I didn’t panic. I began M.A. studies at the Hebrew University and was elected to the Arab Students Union there, which led the resistance to the forced ‘protection’ of Arab students in 1974-1975.

“All along I was haunted by the story I’d heard from my father and from others in the village. When I told [Jewish] students about it, I always got the same response: ‘We didn’t expel anyone and the only massacre was in Deir Yassin [outside Jerusalem, in 1948]. The Palestinians simply fled.’ The silencing and denial of the Nakba prompted me to write an article titled ‘Letter to an Israeli Friend,’ which was published in Haaretz in June 1984.”

The article began with a concise description of the events in his village in 1948, his philo-Zionist schooling and the shock Manna endured when he learned, while taking part in demonstrations against Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, that two of his cousins from Ein al-Hilweh were incarcerated in the IDF detention facility at Ansar in southern Lebanon. Shattered by the news, he decided to abandon his doctoral studies and devote himself to writing a book about the Nakba.

“My wife was shocked,” he recalls. “‘Are you out of your mind? What will you do with a book like that? You have to finish your doctorate,’ she insisted. It was a rough year, 1984. There was a stormy campaign for the Knesset elections, the members of the Jewish underground who perpetrated terrorist acts in the territories were arrested – all of which diverted my attention from [the thesis topic of] the administration and society in the Jerusalem district between two invasions: Napoleon in 1799 and Muhammad Ali in 1831.”

Nevertheless, Manna received a Ph.D. degree cum laude, and subsequently did postdoctoral research at Princeton, where his daughter, Jumana, was born, in 1987. He and Aziza then spent another year abroad, at Oxford, before returning to Israel in 1989. At this point he realized that an academic career was not in the offing: “The Hebrew University offered me a one-year untenured lectureship in the Middle East Studies Department, and I would write a research paper on 19th-century Egypt, and then ‘we’ll see.’ I decided to concentrate on my research of the 1948 war.”

The Mannas’ first priority was their children’s education. They both worked, and one salary went to pay the high tuition for their three children at the Anglican International School in West Jerusalem, where the lingua franca is English. Manna notes that he and his wife aimed to provide their children with more languages and intellectual tools than Arab children in Israel generally receive. Possibly they had an inkling already then of what the future held for the three.

Manna frequently mentions the support he has received from Aziza. They met in 1974, at the Hebrew University’s Mount Scopus campus, where she was taking Islamic studies. After her marriage she studied early-childhood education and worked a coordinator and instructor in that sphere in the Arab community under Hebrew University aegis. Adel, currently a senior research fellow at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, was initially involved in the administration and management of the Center for the Study of Language, Society and Arabic Culture at Beit Berl College in Kfar Sava. Afterward, he headed the Center for the Study of Arab Society in Israel at Van Leer until 2007. From 2009 until 2012 he was the director of the Academic Institute for Arab Teacher Training at Beit Berl.

“From my perspective,” he says, “that was the closing of a circle with regard to the Shin Bet, whose agent in Haifa assured me in 1972 that I would never be a teacher in Israel because of my political activity.”

He and his wife live in Shoafat, a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem. Ironically, their children have not remained here: All three left the country. The eldest, Fadi, 41, a lawyer who has three children, lives in the United States, where he is vice president and associate general counsel at HP. Shadi, 37, is a software engineer; he and his wife live in Barcelona. Jumana Manna, an artist and film director, divides her time between Berlin and Jerusalem. Her 2015 documentary film, “A Magical Substance Flows into Me,” is a look at musical traditions of ethnic communities in Jerusalem in the 1930s, as compiled at that time by Jewish-German ethnomusicologist Robert Lachmann.

“We’ve remained alone,” Manna says. “It’s part of the harsh reality here. My son Fadi advanced to a professional level that an Arab in Israel cannot attain. Shadi worked in Israel for a time, but felt that he was constantly being reminded of the ‘privilege’ that had befallen him as an Arab to be employed in software engineering. Finally he got fed up and told me, ‘I don’t want to be the Jews’ Arab.’ He went to the U.S., earned an MBA and got a job with an American company.”

Do your children think that you’ve stayed in Israel at the price of being “the Jews’ Arab”?

“Our children understood that few options were available to us. As a member of the old generation, I am one of those who remained. In their perception, I somehow got used to the Jews and to their treatment of Arabs. They think that despite my origins in my father’s house, as the son of a construction worker who raised nine children, and even though I worked very hard and received a doctoral degree cum laude, perhaps I didn’t get tenure because I’m a Muslim. I don’t know. The children did not want to go through a similar experience or feel inferior to the Jews.”