Chat became a lifeline for a doctor fighting to save his patients injured by Israeli attacks near and against the hospital itself

In late January, we helped organize a group chat between physicians from across the globe and Dr Khaled Alser, the only general surgeon remaining at Nasser hospital in the south of Gaza.

Less than a year ago Nasser hospital had been the base of 10 surgeons and 10 surgical trainees. Now the 31-year-old Alser, a recent graduate of surgical training in Gaza, was the lone surgeon leading a diminished team confronting a tsunami of trauma patients without many of the specialists or resources we take for granted at trauma centers around the world.

They had very limited medications or medical equipment and had to deal with interruptions with basic services such as power or water. However, the team was committed to providing as much as possible the standard of care they had learned in medical school and training, and Alser reached out to Palestinian doctors (including the author Osaid Alser, a relative) abroad to expand the group.

Early in the life of the group chat, we reviewed a series of cases of civilian trauma patients from military weaponry. Alser shared with us the emergent abdominal exploration of a three-year-old girl following an Israeli airstrike to her home that required repair of her stomach and removal of her spleen. Pediatric surgeons in the group offered help, and the patient was successfully discharged in good condition.

Alser sent images of the mangled extremity of a nine-year-old child who, we all agreed, would need an amputation of her leg – as more than 1,000 children in Gaza have required since October. We gave advice on how to save as much of her leg, skin and soft tissue to give the child the best possible chance of recovery.

And Alser told us about the 25-year-old man with extensive shrapnel injuries to his neck and face requiring emergent exploration and repair. The team at Nasser received guidance on additional surgical care from otolaryngologists and maxillofacial surgeons who reviewed the CT scan and operative images of the patient’s shattered jaw, and praised the damage control and reconstruction performed by Alser.

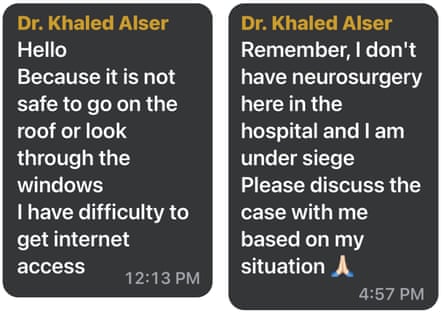

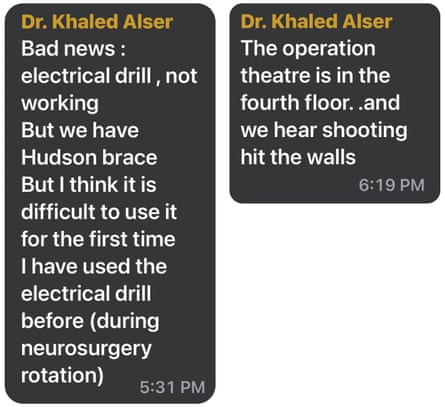

Alser also sought guidance on how to treat many gunshot and shrapnel wounds to the brain while no neurosurgeon was able to reach the hospital amid the Israeli siege. Some injuries were simply not survivable, like the case of a 70-year-old grandmother shot in the head by a sniper. In another case, neurosurgeons in our group helped Alser decide how and when to operate beyond the scope of his previous training, sharing drawings and videos of specialized techniques.

While we reviewed these clinical cases many of us realized the threat looming over the hospital and the doctors on the other end of our group chat. We knew the violence targeting hospitals and healthcare workers was shifting south toward Nasser hospital. But it was still shocking when, in early February, the chat shifted from clinical images of patients to requests that we pray for the staff’s safety.

The last series of messages in the group detailed an onslaught of patients injured on hospital grounds, including a video sent by the surgeon to our chat of an operating room nurse who was shot in the chest while working in the surgical wing of the hospital.

We tried to help guide treatment of this nurse’s injuries based on his imaging and exam findings, as we had with the patients who came before. The doctors also shared video of injured patients in the hospital courtyard who were unable to enter the building because of ongoing shooting until one of the obstetricians, Dr Ameera Elasouli, braved the incoming fire to examine the patient and facilitate their evacuation inside for treatment.

As the security situation of the hospital deteriorated and the internet became spotty, Alser left us audio messages detailing Israeli orders to leave the hospital or face the threat that the hospital would be bombed. He stayed in the hospital with other doctors and nurses to treat his patients beyond the deadline set by the military. The next message was about the subsequent bombing of the hospital that killed one patient in their hospital bed and injured others.

A subsequent attack by an armed drone shot one of the doctors we had been supporting in the head.While this doctor should experience a good recovery, the bullet was centimeters from killing him.

The messages detailed the chaos and terror felt by the hospital staff and patients at that moment, including voice notes with explosions audible on hospital grounds. Despite their best efforts to treat the injured, eventually the staff at Nasser sent us video of the evacuation of the hospital. Alser sent us videos of patients who died when their life support failed because of interruptions of electricity and oxygen imposed during the siege of the hospital. We received no word of the fate of the rest of the ICU patients and premature babies unable to evacuate. We fear their fate may be similar to the premature babies left to die and rot in isolation in al-Nasr pediatric hospital in Gaza City after it was forced to evacuate.

The messages became increasingly erratic and then: radio silence on Thursday, 15 February.

From other news media, we saw images of Israeli soldiers occupying Nasser hospital, placing many healthcare workers in custody and leaving the facility out of service. For three days we worried about Alser’s safety. He eventually responded: “I am still in Nasser hospital among my patients but many of my colleagues were arrested. In short, I lived three days in hell … What happened to the … doctors, patients [and] relatives is unbelievable even in your worst nightmares.”

There is a split in the international medical community over how to engage with the war in Gaza. Many have chosen not to engage at all, but for those of us on this chat, there has been solidarity evolving since October, when the British-Palestinian plastic surgeon Dr Ghassan Abu Sittah stood at a podium at an impromptu press conference surrounded by bodies, civilians killed in an explosion on the campus of the Ahli Baptist hospital.

We remember the Israeli bombardment that killed four department chairs at al-Shifa hospital, including the heads of obstetrics and gynecology (Dr Sereen al-Attar), internal medicine (Dr Rafat Lubbad), emergency medicine (Dr Hani al-Haytham) and pathology (Dr Hosam Hamada).

We heard Shifa’s only nephrologist, Dr Hammam Alloh, when he said to an American interviewer “we are being exterminated”, shortly before he was killed along with much of his family.

We remember Shifa’s senior burn/plastic surgeon, Dr Medhat Saidam, who had been a mentor to one of this article’s co-authors before he was killed along with 30 members of his family in October. Just the day before this group chat was started, two Palestinian medics were killed by Israeli forces when they responded to distressing calls for help from five-year-old Hind Rajab.

Through our phones, we have witnessed in real time the destruction that this war has systematically wrought on Palestinian healthcare workers and healthcare institutions in Gaza.

Shortly after our communications were interrupted with the doctors and nurses in Khan Younis, we read Israeli spokespeople in the news leveling new accusations against Nasser hospital, as they have leveled accusations against one hospital after another in Gaza. This time they have justified the assault by alleging that Israeli hostages had been held in there. It’s almost impossible to refute every accusation that has been made, but it’s clear the intended and actual result of this campaign has been the systematic destruction of the healthcare infrastructure for Palestinians in Gaza, and that has been repeated from north to south.

The UN’s international court of justice has found plausible evidence of genocide in Gaza. While our clinical records may one day be entered as evidence in front of justices in The Hague in line with the Convention on the Prevention and Prosecution of the Crime of Genocide, it will probably not come in time to relieve the suffering of survivors.

It will not treat the wounded, nor bury the dead. It will not return the hundreds of dead healthcare workers to their families, communities and patients.

Our moral obligation as fellow physicians is to support our colleagues in Gaza in their attempts to treat their patients with the care and dignity that all human beings deserve. Without immediate and dramatic action by influential actors on the world stage to end the violence in Gaza, it’s hard to see how that will be possible.

- Dr Simon Fitzgerald is a Brooklyn, New York-based trauma surgeon and surgical intensivist with research experience in injury and violence prevention as well as trauma and general surgery

- Dr Osaid Alser is a Palestinian from Gaza training in general surgery in Texas. He is also a clinical researcher with an interest in global surgery, surgical capacity assessment, and capacity building in war-torn areas and low-to-middle-income countries