Gazans claim the Israeli-controlled area, marked by the so-called Yellow Line, changes without warning, moving west. ‘We are not fighters,’ says one mother sheltering in central Gaza, who worries her children will get caught in the line of fire, ‘we are people trying to live’

When Maha Oudah sends her children outside the shelter where they are staying near Nuseirat, in the central Gaza Strip, she tells them exactly where to stop. There are no fences, no painted border, no official sign marking danger – only a caution she repeats every day: “Don’t go beyond this point.”

Somewhere nearby, she knows, is Israel’s Yellow Line separating Israeli-controlled Gaza from the Palestinian-controlled part of the Strip. But she doesn’t know exactly where.

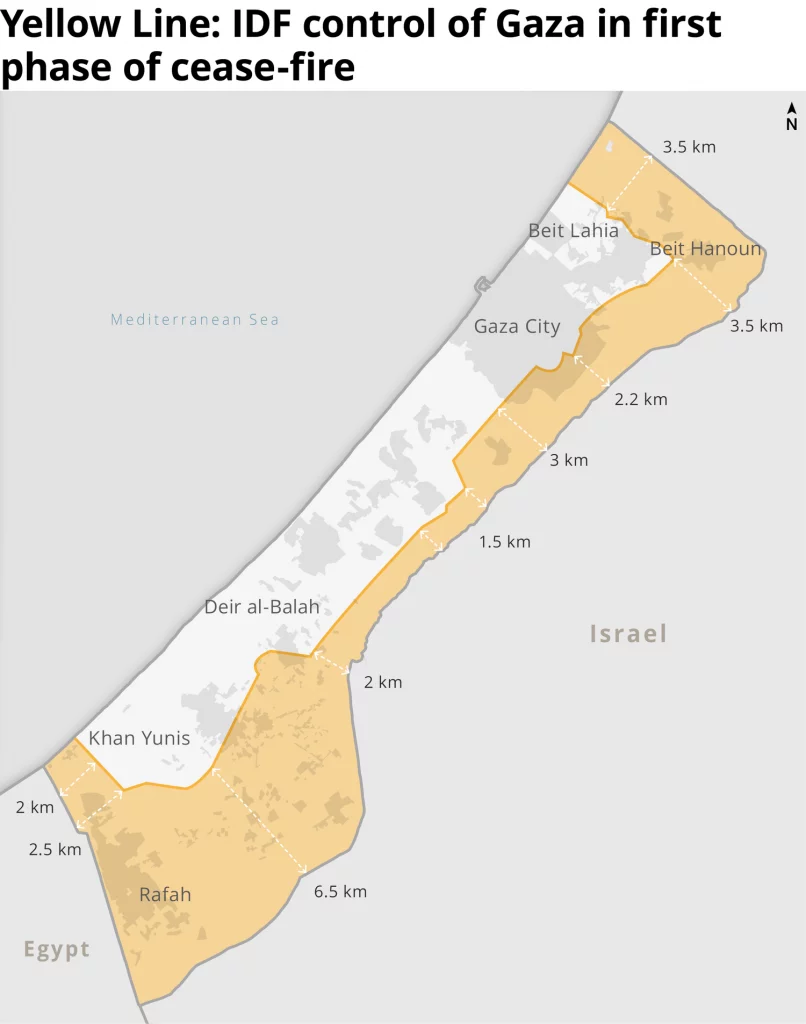

The line – which is marked by yellow blocks – was instituted after the October cease-fire, when Israel pulled out of part of the Strip it had controlled. But across the Gaza Strip, Palestinians describe the steady expansion of the area controlled by Israel and the use of live fire to apprehend those who approach or enter it.

In recent weeks, the Yellow Line has advanced deeper into Gaza’s populated areas, funneling civilians into a tightening geographic area. Residents and humanitarian agencies say the boundary shifts unpredictably, often overnight, and sometimes without any public notice, rendering once-accessible neighborhoods lethal. For residents, the line has become a shifting frontier between life and death.

In eastern Gaza City, near Shujaiyeh and Al-Tuffah, for example, residents say streets that were accessible days earlier are now considered forbidden zones. Similar stories come from Bani Suheila and Khan Yunis in the south, and Beit Hanoun and Jabalya in the north.

“One day the street will be open …. the next day, someone is shot there, and everyone understands the occupation army is there,” Khaled Farhat, a 35-year-old father of three sheltering in Khan Yunis, told Haaretz. Farhat himself has lost 23 members of his family throughout the war. His older brother, Asaad, was killed in an Israeli strike just a week before the cease-fire was announced.

Local medics and witnesses have reported multiple incidents in which civilians – including children and at least one woman – were killed after entering areas that had recently been absorbed into the expanded Israeli-controlled area without updates to residents. In one high-profile case in December, two Palestinian boys, Fadi and Juma Abu Assi, aged 10 and 12, were killed by an Israeli drone strike in the Bani Suheila neighborhood near Khan Yunis while collecting wood for their injured father, according to Gaza medical officials at Nasser Hospital.

The Israeli military said the boys were engaged in “suspicious activity” near its forces and claimed they posed a threat. Palestinians described the boys as civilians performing a basic task of survival. “These were children trying to help their family, and they [the Israeli army] were able to see that they are kids, but their borders don’t recognize a kid, a woman or an old man,” Farhat says.

Since the war began, the vast majority of Gazans have been displaced. By early 2025, UN and partner agencies estimated that nearly 90 percent of Gaza’s population, more than 1.9 million people, had been internally displaced at least once, many several times. According to United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports, since the breakdown of the March 2025 cease-fire, more than 900,000 people have displaced. These figures illustrate how cycles of return and re-displacement are now part of daily life for Gazans.

When the cease-fire was announced, many families returned to their homes, hoping the worst was over. But as the Yellow Line has continued to move westward as the Israeli-controlled area expands, many find themselves facing displacement again. Some newly returned families say they awaken in the morning to find yellow concrete barriers or military vehicles outside their doorsteps; others hear gunfire or shelling close enough to shake the walls. They know that the barrier is getting closer and may eventually encompass their homes.

Na’el ak-Shiakh, a humanitarian worker based in Deir al-Balah, whose family are in another part of the Strip, said that recently they told him they heard gunfire and bombardment all night long. “A few days later, the Yellow Line was visible from their home.” Ak-Shiakh, who is the main provider for his family, added “I can’t afford to rent a [new] apartment for my family, that’s why I can’t imagine them being displaced once again.”

Even before the war, Gaza was one of the most densely populated territories in the world. According to United Nations figures from before the Israel-Gaza war, roughly 2.3 million people lived in a strip of land just 365 square kilometers in size, giving it a population density of more than 6,000 people per square kilometer – higher than almost every country in the world outside of city-states and urban centers.

With the mass displacement brought about by the war, the majority of the population has become concentrated in central areas living in schools, unfinished buildings and makeshift camps. In some UNRWA refugee agency shelters in central Gaza, entire classrooms now house multiple families. Tents are pitched in corridors and courtyards. Privacy is nonexistent.

According to UNRWA, average living space in many displacement sites is only 0.5 square meters per person, far below the Sphere humanitarian standard of 3.5 square meters per person. This extreme overcrowding has led to predictable public health consequences. The World Health Organization and UN health partners have documented frequent outbreaks of acute respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases and skin conditions, especially among children who make up nearly half of Gaza’s population.

Access to clean water in Gaza is dramatically below emergency standards and sanitation services have largely collapsed due to fuel shortages. Sewage pumping stations have shut down and waste accumulates in the streets.

‘Every time we evacuate we start over’

For many families, approaching the Yellow Line is not about defiance; it is a necessity. People say they are forced to go closer to restricted zones to search for food, collect firewood, salvage belongings or look for better shelter simply because resources are so scarce in the crowded central areas. “We are not fighters,” says Oudah, the mother sheltering near Nuseirat. “We are normal, poor people trying to live.”

She is preparing to move again, after hearing nearby gunfire. “We lost everything, and every time we evacuate we start over. We don’t know what to expect anymore, and what tragedy is coming,” she says. “It’s bombs, disease, dirt, we are all going to die at the end, we just don’t know from what.”

For Oudeh, life has become a series of calculations measured in meters: how far children can walk, where tents can be pitched, which streets remain accessible. “We used to think displacement was temporary,” she says. “Now we don’t think that way anymore.”

As the Yellow Line continues to shift, Gaza’s already limited space continues to shrink. What remains is a territory of compressed humanity, where violence and overcrowding have become fixtures of daily existence. “Gaza was already too crowded before,” Oudeh concludes. “Now it feels like the walls are closing in.”

Haaretz has reached out to the IDF for comment regarding Palestinian claims that the Yellow Line is not well marked. The IDF did not provide a response.