‘We try to reveal the subconscious of the dry, bureaucratic document,’ says the movement’s founder

Shmuel Toledano was the Arab affairs adviser for prime ministers Benjamin Netanyahu, Levi Eshkol, Golda Meir and Yitzhak Rabin. In 1970, during Meir’s tenure, he sent a letter to the director of her office describing the steps for introducing censorship against Arabic poetry and literature.

Toledano focused specifically on the writing of Palestinian poet Samih Al-Qasim from the village of Rameh in the Galilee, whom he dubbed an “ultranationalist poet.” The adviser noted that by dint of the 1945 Defense (Emergency) Regulations, restrictions were imposed on what the poet was allowed to publish and that “He is now facing a trial for failing to submit some of his poems to the censor.”

Oppression of Palestinian artists is nothing new, but every archival document like Toledano’s letter enables a deeper understanding of the processes adopted by the State of Israel against the artists and their works.

The Dogme 4.8 project, which was held for the first time last week at Tel Aviv’s Tmuna Theater, consists of performances that make use of official documents from the Israel State Archives, including censorship papers that apply to Al-Qasim’s poems. As part of the project, eight Jewish and Arab artists present a work onstage lasting eight minutes and 40 seconds. Each artist will use two documents: one archival and one contemporary.

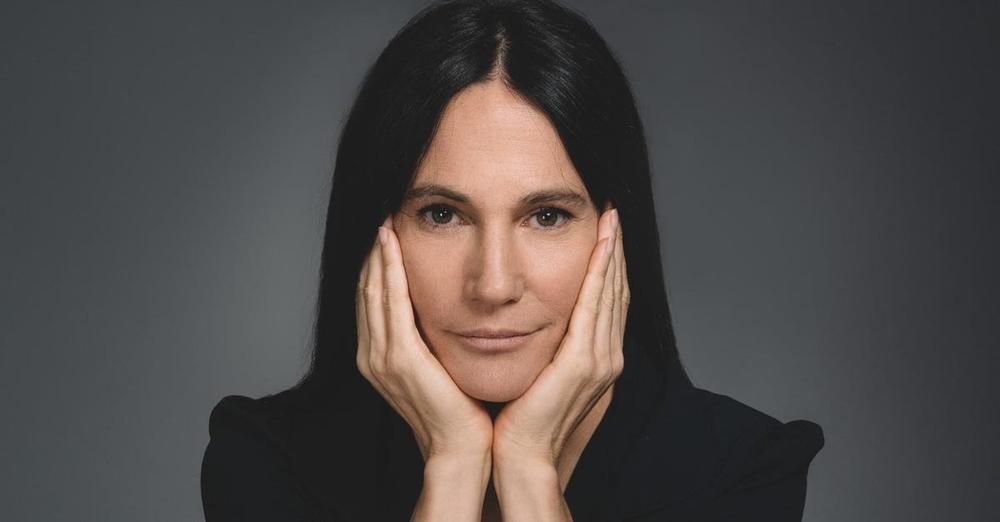

“The work exists between the two documents and points to a process,” says actress and director Einat Weitzman, who is leading the Dogme 4.8 in cooperation with the Akevot Institute for Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Research and researcher Adam Raz. She explains that the project is designed to be a first step in a more comprehensive idea, which is essentially to establish a documentary theater festival.

Dogme 4.8 corresponds, in name and essence, with the cinematic movement Dogme 95 started by Danish film directors Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg. “That was an artistic movement with rigid rules that tried to rethink the form of cinema. I’m trying to rethink theater and its role in times like these,” she says.

In addition to the censorship documents, the performances were also based on official papers that refer to home demolitions, issues connected to the Green Line separating Israel from the West Bank, and political prisoners’ hunger strikes. “The idea was to work with a government archive because it’s like the country’s circulatory system – these are orders, complaints, instructions and remarks,” she says.

One of the participants in the project is rapper and artist Tamer Nafar, who reinterpreted Toledano’s letter and link it to his personal experiences and right-wing organizations’ constant attempts to prevent him from performing. “The practices that were used in 1948 don’t only belong to the past,” he tells Haaretz. “It’s a prolonged process and part of the present, and there’s no reason not to continue talking about it.”

Nafar stresses that the mechanisms that persecute Palestinian artists haven’t changed. “Maybe in the past there was no internet, and they didn’t make a big deal of it and share it on Facebook, but the documents show that the persecution exists,” he says. “Art plays a very important role in resistance.”

Between Hawara and Lod

The censorship of Palestinian poetry and literature is but one step in the ongoing process of oppression. Some of the performances in the project focus on documents dealing with dispossession and the appropriation of land.

The performance of Ala Hlehel, a writer, playwright and director of Hakaya Lab for children’s literature in Arabic, is based on a 1949 letter in which a Palestinian family that fled from the village of Qaddita begs the Israeli government and the Military Administration to let it return to its home. The corresponding contemporary document Hlehel uses in his piece is about the 1999 government decision to build an eco village for Jews in Kadita, located at the former site of Qaddita.

Hlehel breathes life into the documents and through them, emphasizes the balance of power between the Israeli establishment that has taken over Palestinian land, and the Palestinians who are trying to prove their ownership in order to get it back.

The first scene of the play features a discussion between a representative of the Jewish National Fund and a representative of the Interior Ministry in an inter-ministerial committee for official approval of the Jewish community in Kadita.

The JNF representative is angry at a Palestinian who searched the State Archives for a document that will prove that he owns the land, and says: “I don’t understand why he’s making an effort, are these papers going to bring back his destroyed village? Really, let him go see what our guys have done there – a paradise.”

The woman from the Interior Ministry replies that if the Palestinian finds a significant document, the government will have to postpone the approval for the community. The representative replies: “Postpone? Couldn’t he at least have gone early in the morning?” To which the representative replies: “It’s not his fault. He’s been there for a week already.”

The Nakba and the loss of Palestinian land remain burning issues for Palestinian citizens of Israel, 75 years after the country was establish. It’s not surprising that the Arab participants in the project chose to deal with it. “The Palestinian artists approached the plays from a different place. It’s personal and biographical, and that reflects the sometimes obvious oppression of Palestinian Israeli citizens,” says Weitzman.

Most of the documents used for the project are from 1948, she notes. “That’s the year the original sin took place,” she says. “Israel is like a haunted house, and to understand not only what happened in Hawara and Hebron, but what happened in Jaffa and Lod, we have to go back to these suppressed events. Until there is full recognition, these spirits will continue to haunt us.

“A very small percentage of the 1948 documents are open for perusal,” Weitzman says. There’s deliberate concealment here, of course, and there are fewer and fewer people who were alive at the time. Art has to enter this vacuum and revive the documents that are open for perusal.”

Dogme 4.8 also devotes attention to hunger strikes by Palestinian political prisoners, one of the more controversial points in Israeli public discourse – especially after the death of prisoner Khader Adnan last month.

Meira Asher, a sound and performance artist, made a sound installation that traces the sounds the stomach makes during a hunger strike. She based it on archival papers about a hunger strike that took place in Nafha Prison in the 1980s, during which two prisoners died after being force-fed.

“With the art of sound, it’s possible to create all kinds of textures and deep sounds in the body’s tissue,” says Asher. “The goal is to share with the audience the experience the body has during different stages of a hunger strike. There’s a lot happening physiologically there, with very minimalist sound.”

Performance artist Michal Samama presents a document that describes methods to oppress the Palestinian population remaining in Israel’s borders. “For six pages, in a very methodical and orderly fashion, the undeclared Israeli policy towards the Arab minority is explained, as it was formulated by the leadership: From preventing political organizing to holding military exercises in areas where Arabs lived, and up to channeling teenagers to vocational schools instead of academic schools,” says Raz.

The document was composed in the early 1970s, Raz says, and is a summary of a number of discussions that took place between Prime Minister Golda Meir’s deputy, Yigal Allon, and the Central Security Committee – a body that made decisions on Arab citizens during the period in which they were subject to martial law. Weitzman says that this is one of the most difficult documents in the project to deal with.

“Documents of this type give themselves cover,” he says. “The performance tries to reveal the subconscious of this dry, bureaucratic document. Art is extremely powerful. It’s capable of revealing the significance of this suppressed document.”