Israeli freedom of speech is being called into question, and that’s pretty ironic

What’s the exact measure of “Israeli democracy” these days? For that, it’s helpful to get a reading through the lens of a Palestinian.

Mai Da’na lives in Hebron. Late on a winter’s night in February 2015, Israeli soldiers entered her home. For Palestinians in the West Bank, this is an everyday part of life: As the Order Regarding Security Provisions stipulates, “An officer or a soldier is authorized to enter, at any time, any place” No search warrant is required, no legal standards such as “probable cause” or “reasonable suspicion” are even relevant.

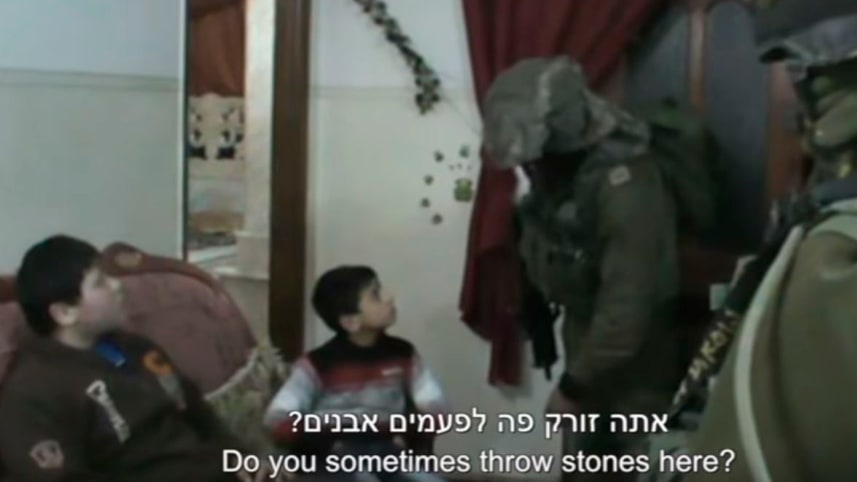

In occupied Palestine, Giorgio Agamben’s constant state of exception is not philosophy: It is reality. In fact, this reality has been going on for 50 years, almost double 26-year-old Da’na’s lifetime. To fully grasp its meaning, one need only watch the video she took that night, when soldiers barged into her home, demanding that her young children be awakened.

Unlike Da’na, I am a Jewish, Israeli citizen. I live in West Jerusalem. My situation is very different, in the million ways in which the lives of subjects and the lives of masters diverge. And yet, our spaces are interconnected.

In recent years, Da’na began volunteering with B’Tselem’s Camera Project. Women videographers have consistently distinguished themselves among the 200 or so volunteers in this citizen journalism project, which aims to depict the reality of the occupation. So, it was no wonder that, in August 2017, when the project marked its 10th anniversary, B’Tselem decided to present at the Jerusalem Cinematheque a program entitled “Palestinian Women, From the First Intifada Until Today,” featuring footage entirely shot by women – including the video by Mai Da’na.

Screening the reality of life on one side of the Green Line on the other side of that line is easy enough. But what crossed the line through that screening was much more than only those images from Hebron and other West Bank locations. Following that evening, the Israeli Ministry of Culture very publicly wrote the Ministry of Finance, demanding that funding for the Jerusalem Cinematheque be re-examined in light of its screening of films by B’Tselem volunteers. The legal basis for such a demand was codified by the Knesset back in 2011, in the shape of the “Budget Foundations Law (Amendment 40): Reducing Budget or Support for Activity Contrary to the Principles of the State.”

In recent months, Culture Minister Miri Regev has been waging a campaign against artists, screenwriters, theaters – and yes, cinemas – that dare to go ahead with events, plays or films that “incite against Israel.” According to Regev, showing the truth about Israel’s rule over Palestinians is incitement.” She wishes to exercise what she calls, in true Orwellian fashion, “freedom of funding”: the liberty not to fund artistic speech that deals with that constant state of exception in effect just a few kilometers away from the Jerusalem Cinematheque.

Non-options, non-citizens

Citizens – especially Jewish citizens – living on the Israeli side of the Green Line are generally used to exercising their free speech rights. But in occupied Palestine, free speech has been a non-option ever since August 1967, two months after the occupation began, when Order No. 101 was issued. Its point of departure is that Palestinian residents have no inherent freedom of protest or freedom of expression, and that even nonviolent resistance and civil protest involving peaceful assembly are forbidden. For 50 years, we have been defining almost any Palestinian opposition to the occupation regime as incitement, while denying basic human freedoms as free speech. Is anyone really surprised that the screening of a video collection focusing on the occupation is now framed as – of course – incitement, and that the freedom of speech of Israelis is being called into question? One cannot deny the irony in this process, which brings Israeli and Palestinian NGOs and activists closer: not because the civil space is widening in occupied Palestine, but because it is shrinking in occupying Israel.

Of course, for the millions of Palestinian non-citizens, with no political rights, whom we have been ruling by military decrees for decades, democratic space collapsed long ago. The casual vulnerability of Palestinian homes is just one example of how fragile life can be, in a place where Israel controls with impunity through arbitrary administrative decisions people’s ability to travel abroad, receive a work permit, get married, access their land, build a home – to name just a few examples.

And what of life in Israel? Equating NGOs that oppose the occupation with treasonous servants of suspect foreign powers has become routine, from the prime minister down. In this current reality, an ongoing blend of intimidation, infiltration and legislation is the new normal. The need to maintain the appearance of democratic norms has now been mostly set aside, replaced by a political appetite to demonstrate to a cheering public that the government is after the fifth column.

The efforts led by the culture minister are only a few of many like-minded initiatives. Together, these spell out the shrinking of space for free speech and for civil society. It is a process that took place mostly in the last seven years, moving forward parallel to similar downward spirals in places like Hungary, India and Turkey. The rising authoritarianism in Jerusalem can be spotted even from as far as Berlin: In June 2017 a spokesperson for the German Foreign Affairs Ministry said of Hungary that it has joined “the ranks of countries like Russia, China and Israel, which obviously regard the funding of NGOs, of civil society efforts, by donors from abroad as a hostile or at least an unfriendly act.” A few months later, Israel had the dubious honor of being featured in the UN secretary-general’s annual report on “Cooperation with the United Nations, Its Representatives and Mechanisms in the Field of Human Rights,” known informally as the “reprisals report.”

Funding cuts

Of all the efforts made to act against human rights NGOs, the most steadfast one has been to try and curtail access to international funding. But the government cannot simply pass a law to which an addendum with the list of undesirable groups will be attached – that would be too blunt. It took several years and a few legislative iterations, until an administrative criterion that would apply almost exclusively to the, well, undesirables was identified: groups with a relatively high percentage of “foreign state-entity funding.” As foreign governments quite obviously are more likely to invest in promotion of human rights than in the advancement of the occupation, by looking at an NGO’s relative funding from such sources, one can assemble a de-facto list of the NGOs the government is after, without having to resort to listing them individually.

The above logic was at the core of the 2016 amendment to the Law Requiring Disclosure by NGOs Supported by Foreign State Entities, which stipulates that groups receiving 50 percent or more of their funding from “foreign state-entity” sources will practically need to identity themselves as foreign agent NGOs. The amendment was initially marketed as “advancing transparency.” Yet that was never the real issue, as NGOs were already required by law to make a public annual report of all donations they received of 20,000 shekels (about $5,900) and above. Moreover, since 2011, non-profit organizations are required to file quarterly reports of all donations from foreign state-entity sources. At all events, since the law was passed, it has served as the staging ground for further legislation, completely removed from “transparency,” but rather quite transparently about yet more public shaming and administrative limitations and burdens on human rights NGOs.

The amendment does not prevent receipt of foreign funding. However, in June 2017, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly confirmed that he had tasked Tourism Minister Yariv Levin with formulating a new bill that would block foreign governmental funding to nonprofits, in an effort explicitly targeting human rights groups opposing the occupation. Minister Levin explained to Haaretz the change in the government’s position, from promoting a bill that did not limit foreign governmental funding to seeking legislation that would block it. He explained that the new U.S. administration has made it possible: “It wouldn’t have made it through in the period of the Obama administration. They were very uneasy about the bill. The present administration has no problem with it.”

Crossing the line

Palestinians cannot easily cross the Green Line and enter Israel: special permits are needed. Authoritarian thinking, however, needs no such permit, a green light from the powers that matter will suffice. Similarly, the winds blowing from Washington appear to be felt on both sides of the Green Line. A few weeks after Levin’s interview, it was Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman who used almost identical language – but now in the context of actions on the other side of the Green Line, namely, the possibility of going ahead with the demolition of entire Palestinian villages – Khan al-Ahmar, east of Jerusalem, and Sussia in the South Hebron Hills.

Mai Da’na’s footage also crossed the Green Line. Its modest screening in Jerusalem to an audience of 100 or so viewers was sufficient to trigger a McCarthy-style governmental review of one of Israel’s most established cultural institutions. For, to enable further oppression of Palestinians, stronger silencing of Israelis is now deemed necessary. Our fates are intertwined.

Similarly, the international mechanisms that somewhat delayed these developments are intertwined. Not only are many international actors used to taking their cue from Washington – now under Trump – but Israel’s leadership is also currently empowered by the favorable winds blowing from the rising authoritarian powers across the globe.

As rightfully worrying as these negative developments inside Israel are, they are not the reasons why the country cannot be considered a democracy. For that, we need not focus on recent years, but open our eyes to the past half century. Israel’s rule over millions of Palestinians with no political rights has been in effect for all but the first 19 years of Israel’s existence as an independent state. That is why Israel is not a democracy, and indeed has not been one for many a decade. We live in a one-state reality between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, a state whose constant state of exception is one of masters and subjects, of millions with political rights – and millions without.

Yet, here is what I genuinely embrace: Yes, the authoritarian global realignment is real. If you have any doubts, just listen to Netanyahu, Trump, Modi, Orbán, and the many others contending to join their ranks. But it is not preordained that this will be the only global realignment witnessed by humanity in the 21st century. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is too precious an achievement, won after unimaginable human suffering. We know what is at stake. We might as well stand together so that “the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” are realized, so that “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” is rock solid. There are no assurances of success: only the certainty that it is a future worth fighting for.