Human rights advocates say even MLK and Mahatma Gandhi would not be recognized as conscientious objectors based on the IDF’s definition of the term. Academics on the committee, activists, objectors and lawyers tell Haaretz how the military system deals with defiant refusers

“The IDF isn’t a fair place,” Tal Mitnick said from the prison pay phone late last month. “And I don’t expect it to be fair.”

In his army uniform, the summer heat was scorching the military prison grounds as he spoke. That was his one call for the day. Afterward, Mitnick – the first Israeli to refuse the draft since war broke out with Hamas last October – would return to his seven-person cell until dinnertime.

Conscientious objectors commonly serve three to four months behind bars as punishment. But Mitnick, who spent more than half a year in a military prison on successive terms before being released last week, is an unusual exception. With millions of views online, Mitnick, 18, is one of Israel’s most high-profile Gen Z peace activists.

Objectors like him are often imprisoned by the Israel Defense Forces repeatedly for the same offense. Tied up in monthslong legal battles, they face a shadowy system of military justice – one which human rights advocates say violates international law and basic standards of due process.

Some plead their case before the Conscience Committee, a rotating panel of three military representatives and a civilian philosopher from the academic world. Their goal is to officially be recognized as conscientious objectors under Israeli law, which takes convincing the military tribunal that they are pacifists. If successful, they earn their freedom in the form of a draft exemption.

The process, though, is anything but simple. Israel’s legal definition of a pacifist is so narrow that even Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. would fail to qualify, according to Michael Sfard, a leading human rights lawyer who has represented hundreds of objectors. The IDF still hasn’t formally recognized Mitnick as a conscientious objector.

‘They will pay a price’

Those who refuse the draft as a political statement against, say, the occupation or how the military has waged its destructive war in Gaza are less likely to pass the committee.

In Israel, being “driven by a deep sense of justice” doesn’t necessarily equate to being recognized as a conscientious objector, said Prof. Noam Zohar, a philosopher on the committee who teaches at Bar-Ilan University. He used Rosa Parks – who in 1955 refused to give up her seat to a white man on a segregated Alabama bus – as an example of a protester who likely wouldn’t pass the committee today. “She expected to go to jail for that,” he said. “And she did.”

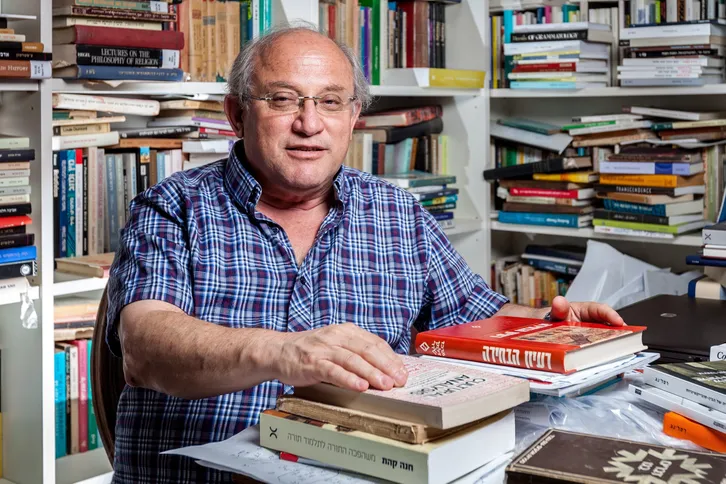

Draft refusers “should know they will pay a price” for civil disobedience, said Prof. Avi Sagi, another philosopher on the rotating committee who also teaches at Bar-Ilan University. “It’s not that I like the price.” Violating the law, Sagi said, even for a just cause, comes with consequences.

At a recent hearing, an objector told the committee he had declined to serve because he was disillusioned and wanted to spark political change. “I praised him and told him I wish all the citizens of the State of Israel were like that,” Sagi said. “We would get rid of a problematic government that is leading us to dictatorship and disaster.”

Nevertheless, Sagi voted against recognizing him as a conscientious objector.

Critics say how the committee distinguishes between pacifists and political activists is largely arbitrary. Committee members sometimes disagree on precisely where that line is drawn as they probe objectors for their motives.

The committee’s guidelines, which Haaretz obtained, are not published anywhere and contain no specific instructions on how to differentiate civil disobedience from conscientious objection.

Sagi, who co-authored the IDF’s current code of ethics, admitted that the committee hands down decisions entirely on a case-by-case basis, with no definitive standard of proof for finding that someone is or isn’t a conscientious objector. “When I’m in charge of a dialogue with you, it’s not a matter of proof,” he said.

Prof. Avi Sagi said his work on the committee is inspired by one of history’s most notable advocates of civil disobedience: Henry David Thoreau. According to Sagi’s interpretation, he has a duty to help judge objectors – and for an objector, being jailed is how they can advance their cause.

The committee weighs moral questions, not legal ones, which is why, according to him, the rules governing a typical courtroom don’t apply and objectors are not allowed to have their lawyers participate during questioning.

Mitnick told Haaretz that he had known going into the Conscience Committee that he would have a tough time. He met with the committee twice, the second time on appeal last month, to argue that he should be considered a conscientious objector. He was denied both times. “I was not allowed to truly express my opinion,” Mitnick said of the hearings.

He described the lines of questioning he faced as confusing and confrontational, with subject matter ranging from veganism and taxes to unfamiliar historical figures. The committee tried “to trip me up,” he said.

For evidence against him, the committee brought in large binders filled with copies of his social media posts and news interviews. One of the hearings, he recalled, amounted to a face-off with Sagi, who strung together arguments to suggest that Mitnick was not generally opposed to war – a claim the self-avowed pacifist denied.

When Sagi spoke, the military representatives around him would smile, Mitnick said, and one told Sagi under his breath something to the effect that the professor “broke” Mitnick.

“I don’t remember. It’s disgusting if it was said,” Sagi said, declining to comment further on Mitnick’s case.

‘Tricky on purpose’

Noa Levy, an objector-turned-lawyer who represents Mitnick and others like him, told Haaretz that the process is so shrouded in secrecy that “it should be illegal.” For an objector to apply for a hearing with the Conscience Committee, they first need an affidavit signed by a lawyer, Levy said, though that requirement “isn’t written anywhere.”

Sofia Orr, the second Israeli teenager after Mitnick to refuse the draft since October 7, described the questions – most of which, she said, were asked by Sagi – as “tricky on purpose” and “very shallow.” Oftentimes, the committee would cut her off before she could finish answering.

“If it were October 7 and IDF soldiers saved you, would you have been grateful?” Orr recalled being asked. “Or would you have preferred to die because they used violence to save you?”

Orr was ultimately granted conscientious objector status last month, bringing her 85 days in military prison to a close. As a 19-year-old vegan who wouldn’t “even step on a fly,” she said she “fit the type they were looking for” and had to play up aspects of her identity to be released from mandatory conscription.

She also suspected that sexism may have played a part. Despite being similarly opposed to military violence and having protested the Israel-Hamas war side by side with Mitnick, the two had starkly different outcomes: One passed the committee on her first try; the other failed twice.

“They have a way easier time being convinced that a woman is a conscientious objector,” she said. “They wanted to make an example out of him.”

Sagi dismissed the accusation of gender bias as “nonsense,” but did not provide a concrete answer when asked about what guardrails the committee had in place to prevent discrimination.

“Nonsense” was the same response he gave when asked about critics who say the Conscience Committee goes against international law.

In a report released last year, Amnesty International noted that Israel’s military justice system violated rules established by the United Nations prohibiting double jeopardy and viewpoint discrimination against conscientious objectors. The Conscience Committee, the report found, “frequently rejects pacifists’ cases.”

Zohar, the committee member, was surprised to hear that international law on conscientious objection exists. “I do not know of any international law about that,” he said. “I should admit that my expertise is in ethics, including ethics of warfare, but not in international law.”

For his part, Sagi seemed unconcerned by the human rights group’s complaints, simply saying, “Amnesty can write what they want.”

In his view, today’s Conscience Committee is fair – and an improvement on the past. Until the early 2000s, when Sagi was introduced as one of its first civilian members, the committee was made up of Defense Ministry retirees who, Sagi said, were biased against objectors and had no professional training whatsoever.

Sagi and Zohar both said the committee now recognizes most who come before it as conscientious objectors, but neither could provide records or statistics to confirm that. Through a spokesperson, the IDF declined to provide those figures.

Sfard, the human rights lawyer, remains skeptical of Israel’s military justice system. The committee has a history of operating on “unclear standards,” he said, adding that those who fall outside its view of what a conscientious objector is are having their rights violated.

International law “definitely provides for freedom of conscience,” the idea that “people should not be coerced into doing things that undermine their core values,” Sfard said.

A complicated philosophy

Because of how informal the committee process is, complex theories can be what decide cases. Pleading for one’s freedom can quickly turn into a game of mental gymnastics. The committee has been known to use hard-to-follow philosophical arguments.

For instance, Sagi said his work on the committee is inspired by one of history’s most notable advocates of civil disobedience: Henry David Thoreau. Simply put, the 19th-century U.S. philosopher believed that the more soldiers there are who are willing to sit in prison to protest war, the more pressure would be placed on governments to put an end to the bloodshed.

The committee often tests objectors with pedantic and paradoxical arguments, as well as allusions to historical figures, leaving teenagers like Mitnick stumped on the stand.

Sagi’s own interpretation, whether true to Thoreau’s intended message or not, is that he has a duty to help judge objectors – and for an objector, being jailed is how they can advance their cause. But that thinking leaves little room for the dyed-in-the-wool activists who would prefer freedom to prison. And one of Thoreau’s revolutionary-minded stances was that a system is unjust when it punishes conscientious objectors.

“Under a government which imprisons any unjustly,” Thoreau wrote, “the true place for a just man is also a prison.”

Committee members and the IDF have a history going back decades of citing democratic thinkers who backed conscientious objectors, only to use those thinkers’ words against the objectors themselves.

During the second intifada, for example, the IDF was met with a conundrum when hundreds of objectors came forward to protest the occupation. The army’s top lawyer at the time, Menachem Finkelstein, argued that, according to Immanuel Kant’s theory of the categorical imperative, refusing to serve in the IDF is wrong. If every soldier and draftee quit, he said, that would spell the end of Israeli democracy. Kant, however, expressed support for conscientious objection in his writings.

The committee often tests objectors with similarly pedantic and paradoxical arguments, as well as allusions to historical figures, leaving teenagers like Mitnick stumped on the stand. With no legal representation throughout his grilling, Mitnick, who only graduated high school last summer, struggled to keep up with Sagi – a well-established academic nearly four times his age.

“When [Mitnick] tried to make a point, he was being negated by theories he had never heard of,” his lawyer Levy said.

For those like Mitnick who fail to be recognized as conscientious objectors, there’s no middle ground: selective objection is outlawed. In 2002, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled against a group of reservists who said they would serve in the army – just not in the West Bank or Gaza, which they believed would involve “dominating, expelling, starving and humiliating an entire people.”

Like those reservists and many others who came before him, Mitnick is vehemently opposed to the occupation and intent on challenging one of the world’s strongest armies over his beliefs. To him, what the committee has to say doesn’t change that. “The only way to know if I am a conscientious objector,” Mitnick said, “is inside me.”